Russia’s assertive Svalbard claims increase tensions with Norway, threatening stability in the Far North.

In a nutshell

- Russia steps up Arctic efforts, challenging Norway’s control over Svalbard

- The Kremlin is reviving settlements and conducting military activities

- The 1920 Svalbard Treaty limits Norway’s sovereignty

- For comprehensive insights, tune into our AI-powered podcast here

The standoff between the United States and Denmark over Greenland has heightened concerns about Arctic security. Although the idea of the U.S. purchasing the island was previously dismissed, it has resurfaced amid President Donald Trump’s claims that America must take control of it for strategic reasons. This time around, the conversation carries a troubling implication: The White House has not ruled out the possibility of using military force.

Even if it ultimately fizzles out, the Greenland gambit has already caused fallout elsewhere in the Arctic – prompting something far more concerning than a rift in U.S.-Denmark relations. It has emboldened Russia’s ambitions in the Norwegian Svalbard Archipelago.

Russia’s calculated play for Svalbard

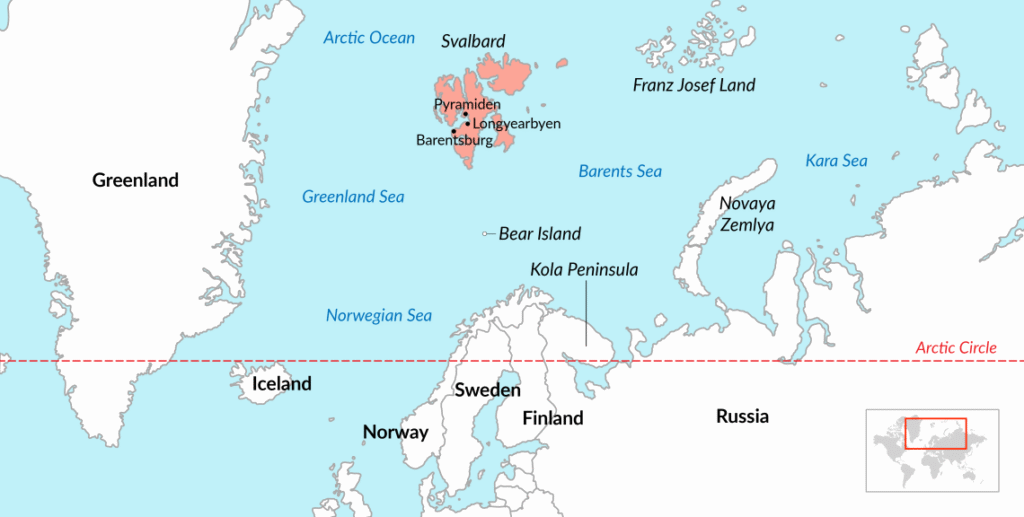

Drawing inspiration from the American rhetoric on controlling Greenland, Russia has ramped up its own claims over Svalbard. Situated midway between the North Pole and the Norwegian mainland (about 1,000 kilometers away from its northernmost city of Tromso), this remote area once attracted little attention. However, that changed with the melting of Arctic ice, opening new possibilities for hydrocarbon exploration.

Russia has repeatedly claimed that Norway is misusing its rights to the continental shelf around Svalbard. Nevertheless, in the broader context, the hydrocarbon debate is more of a sideshow.

The primary reason why control of Svalbard is even more important than the contest for Greenland is its strategic location. Much has been said about the significance of the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom Gap, which separates the Norwegian Sea from the Atlantic Ocean. In times of crisis, the Russian Northern Fleet’s ballistic submarines would have to navigate through this heavily monitored chokepoint. The Svalbard archipelago, including Bear Island at its southernmost tip, offers an even more advantageous position for monitoring Russian access routes into the Atlantic.

Facts & figures

Svalbard: Strategic gateway to the Arctic

Russia is deeply concerned that Norway – and NATO – may consider militarizing Svalbard, which could lead to the use of its port facilities as a logistical hub for warships. Additionally, the airstrip in Longyearbyen – a small settlement on the archipelago’s largest island, Spitsbergen – could be utilized for alliance strike aircraft to secure air superiority and for long-range patrol aircraft to bolster monitoring of the Barents Sea and Russia’s Novaya Zemlya archipelago, which is vital for Russian strategic weapons testing. Furthermore, sophisticated radar and air defense systems could be deployed to protect such military assets.

Russia has formally accused Norway of militarization, a claim that the Norwegian government has firmly denied. This follows the classic Russian playbook, namely, creating a pretext for actions that serve their own interests.

Given that Norway is a founding member of NATO, Svalbard is widely considered to be under unquestionable U.S. protection. However, that assumption may no longer be taken for granted.

Some have speculated that there could be a tacit agreement between Washington and Moscow, where the U.S. gets Greenland and Russia gets Svalbard. In a parallel to a proposal by a U.S. lawmaker that Greenland should be officially renamed “Red, White and Blueland,” a Russian lawmaker has proposed referring to Svalbard as the Pomor Islands, citing historical connections to support the change.

Although President Trump’s actions may fuel conspiracy theories, in the case at hand, active collusion is not even necessary. If Russian President Vladimir Putin only believes the U.S. will not intervene, he may feel emboldened to act against Norway. A Russian incursion into Svalbard would directly challenge NATO, bringing the pivotal issue of the credibility of Article 5 on collective defense to the forefront. Alongside its ongoing hybrid tactics against NATO member states, the Kremlin is likely to test these boundaries simply to gauge how far it can push.

Norway’s sovereignty over Svalbard

Regarding Greenland, Denmark has steadfastly maintained its position with strong resolve. Considering the declared U.S. interest in accessing the island’s mineral resources, it is crucial that Copenhagen focuses on strengthening European interest in Greenland, which is under home rule and not a member of the European Union.

During a mid-May trip to Brussels, Greenland’s Foreign Minister, Vivian Motzfeldt, stated that she was seeking to deepen bilateral ties with the EU, highlighting rare earth minerals as a starting point. Days later, it was announced that a Danish-French mining group received a 30-year concession to extract anorthosite, a white rock that could serve as a climate-friendly alternative to bauxite in aluminum production.

While this might appear to be a setback for the White House, the Kremlin holds stronger cards. Unlike Denmark, Norway faces two key vulnerabilities that Russia has been adept at exploiting. The first is the limitation of its sovereignty over Svalbard due to an international treaty.

The status of the archipelago was resolved with the Svalbard Treaty (originally the Spitsbergen Treaty) of 1920. Ratified in 1925, it granted sovereignty to Norway under strict conditions. The archipelago was to stay a demilitarized zone, with no permanent military presence permitted, and all parties to the Treaty (now nearly 50, including Norway, the U.S., Russia and Japan) were to have equal rights to commercial activities.

The strategic importance of Svalbard became clear during World War II, when it served as a hideout for German submarines targeting Allied convoys delivering supplies to Murmansk, Russia. In the post-war era, it has been rather sleepy. Today, the population of Svalbard is just under 3,000, roughly equal to the estimated number of polar bears in the region. While Norwegians make up a slight majority, the diverse community also includes residents from around 50 countries.

The Russian presence in Svalbard was sustained for a long time through mining activity, leading to the establishment of two small Russian settlements, Barentsburg and Pyramiden, where the furthest-northern statues of Lenin in the world can be found. During the 1980s, these settlements saw a revival as Moscow took an interest in the Far North. However, in the 1990s, they were abandoned and became ghost towns, reminiscent of the old Soviet Union.

Norwegian coal mining activities were suspended in 2017 and shut down by 2020. By that point, however, Russian security interests had already begun to overshadow the mining interests. In its 2016 security doctrine, Russia identified Svalbard as a potential naval conflict zone, and during its September 2017 Zapad war games, there were reports of a simulated airstrike targeting Svalbard.

Direct provocations have included Chechen special forces using Longyearbyen airport as a transit point en route to an airborne drill at the North Pole, and Russian Special Operations Forces briefly appearing under the cover of darkness. In 2022, a Russian trawler was suspected of severing crucial underwater cables by dragging its anchor across them.

Another concern is the importance of fisheries to the Norwegian economy – it is one of the largest fish exporters in the world. This was likely the main reason why the Norwegian people voted against joining the EU. Since much of the fish stock’s breeding grounds are in waters near or controlled by Russia, escalating tensions could prompt Moscow to target this vital resource.

Oslo’s diplomatic tightrope

Norway also has a long history of close cooperation with Russia on non-strategic issues. Before NATO’s eastern expansion, it was the only member that had a land border with Russia. Located just a few kilometers from the border, the Norwegian town of Kirkenes has hosted many routine meetings where emerging problems have been resolved. Besides fisheries, Oslo and Moscow also share crucial common interests in matters ranging from sea rescue to environmental monitoring and protection.

Following the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, forums like the Arctic Council and the more narrowly focused Barents Council have been closed to Russian participation. However, Norway has hesitated to sever ties entirely. As a non-EU member, it cannot be formally charged with violating the sanctions regime, yet the Oslo government has faced growing criticism for allowing Russian ships, including those from its infamous shadow fleet, to dock in Norwegian harbors. These ships have been permitted to change crews and replenish their supplies.

Scenarios

Unlikely: Norway pursues militarization of Svalbard

In one scenario, Norway decides to take a firm stance and directly confront Russian provocations. It could choose to close all its ports to Russian ships and ensure that any vessels considered part of the shadow fleet are also prohibited from entering.

It could respond to trawlers dragging their anchors across underwater cables by taking military action against terrorism. Oslo could declare that any further Russian violations of the Svalbard Treaty will give Norway the right to pursue militarization. It could also ensure that it has full U.S. support for taking such decisive actions. Since the latter is unlikely to happen, none of the above is very probable.

Likely: Russia escalates political pressure on Norway

An alternative scenario is that Russia escalates its complaints against Norway and takes further action to advance its own interests. A comparison can be made to the Swedish island of Gotland, located centrally in the Baltic Sea, which was so strategically important during the Cold War that it was nicknamed the “unsinkable aircraft carrier Gotland.”

Even aside from concerns that a Russian attack on the Baltic States would include a move to seize Gotland, the Swedish government faced serious pressure. The Kremlin argued that the island is so strategically vital that no single country must control it. The preferred solution was demilitarization and a joint control regime that gives Russia substantial influence.

In the post-Cold War era, Sweden’s position was weakened by its own unilateral decision to effectively demilitarize the island. It was also telling that when the Nord Stream consortium was granted permission to build pipelines in the Swedish economic zone, they were allowed to use a port facility on the east coast of Gotland to support their pipelaying activities. When the Swedish military requested that the port extension be wired for demolition, Moscow denied that request.

A Russian move against Svalbard would follow precisely this path, and Svalbard is considerably more vulnerable than Gotland, which is currently being re-militarized. Signs of Russia’s intentions include the Russian Consul General leading a Victory Day parade in Svalbard on May 9, 2023, and the planting of three Soviet flags in 2024 – one at Barentsburg and two at Pyramiden – in defiance of Norwegian sovereignty. The Kremlin also has plans to modernize public infrastructure in the settlements.

More significantly, Russia intends to establish a research station in the archipelago and invite BRICS members to participate. As China looks to expand its influence in the Arctic, this is a clear invitation to Beijing.

Given that Russia’s dedicated Arctic brigades have been severely damaged in Ukraine, and that its main amphibious assets have been destroyed by Ukrainian drones, a full-scale military attack is not on the cards, but political pressure is bound to increase. How far Russia will go depends on the Trump administration.

For the moment, Oslo is acting with cool composure, but there is obvious concern. Claiming it is not interested in a new cold war in the Arctic, Russia has dangled the lure of a comprehensive “deal.” If President Trump agrees to pursue that path, Norway will come under intense pressure.