The area affected by oil and gas production and mining in the Arctic is growing every year, as a new study by the University of Zurich shows. In addition to night-time light pollution, industrial activities lead to numerous other problems for nature and the environment.

Oil, gas, nickel, palladium, platinum, copper, zinc and many more – resources that the world craves. Extracting them demands immense energy and often comes at a high environmental cost, especially in the Arctic, which has warmed nearly four times faster than the global average over recent decades.

A new study led by Professor Gabriela Schaepman-Strub from the Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies at the University of Zurich now shows how quickly industrial development is progressing in the Arctic and with it the destruction of habitats. The results were published on October 21 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

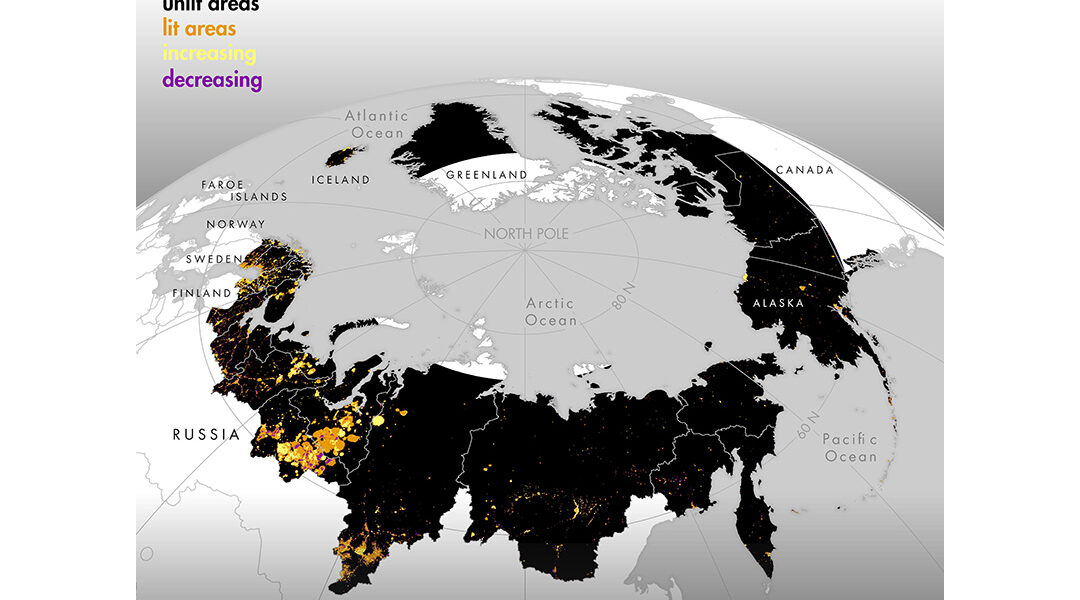

The international research team analyzed nighttime satellite images to identify and measure hotspots and trends in human activity across the Arctic from 1992 to 2013, using artificial light as a key indicator.

“More than 800,000 square kilometers were affected by light pollution, corresponding to 5.1 percent of the 16.4 million square kilometers analyzed, with an annual increase of 4.8 percent,” says Prof. Schaepman-Strub in a university press release.

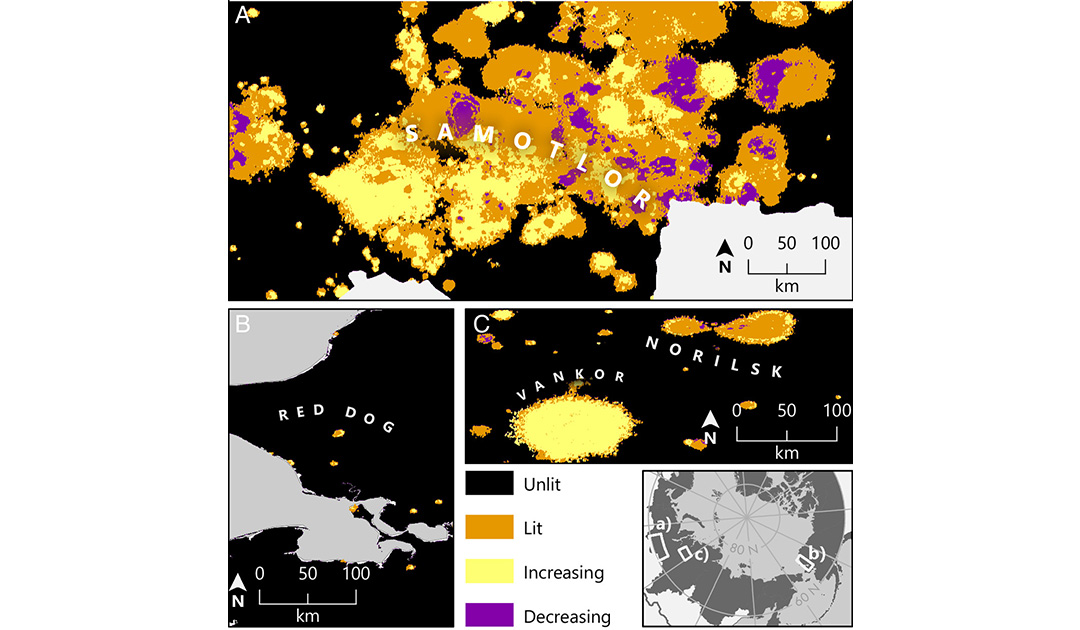

The research team identified artificially illuminated areas primarily in the European Arctic and the oil and gas production zones of Russia and Alaska, where up to a third of the land area in these hotspots is lit. In contrast, the Canadian Arctic shows only a few small zones with nocturnal human activity.

“We found that, on average, only 15 percent of the lit area in the Arctic contained human settlements, which means that most of the artificial light is due to industrial activities rather than urban development. And this major source of light pollution is increasing in both area and intensity every year,” explains Cengiz Akandil, PhD student in Prof. Schaepman-Strub’s team and first author of the study.

However, the industrial activities have different impacts. The study shows that the oil and gas industry in the Arctic causes significantly greater light emissions compared to mining. While both industries cause physical disturbance and long-term environmental damage, the spatial spread of light pollution from oil and gas production is far more extensive.

Industrial activities and the associated light pollution have a massive negative impact on biodiversity in the affected areas. For example, artificial light interferes with reindeer’s foraging and predator evasion behaviors, as their eyes are less able to adapt to the blue tones of winter twilight. In Arctic plants, which are perfectly adapted to the short growing season, leaf coloration and the opening of leaf buds is delayed by artificial light at night.

“In the vulnerable permafrost landscape and tundra ecosystem, even just repeated trampling by humans, and certainly tracks left by tundra vehicles, can have long-term environmental effects that extend well beyond the illuminated area detected by satellites,” says Akandil.

Environmental pollution from industrial activity is another major concern not only within extraction and mining sites but extends far beyond, impacting areas along pipelines and downstream from industrial hubs like Norilsk in Russia.

In their study, the researchers emphasize that Arctic ecosystems are already highly vulnerable due to rapidly accelerating climate change and that the annual expansion of industrial activity is adding to the pressure. Documenting human activities and differentiating between urbanization and industrialization is therefore essential to support sustainable development in the region.

The team even warns that anthropogenic interventions in the Arctic ecosystem could exceed or at least exacerbate the consequences of climate change in the coming decades. By 2050, 50 – 80 percent of the Arctic could reach a critical level of anthropogenic disturbance.

“Our analyses on the spatial variability and hotspots of industrial development are critical to support monitoring and planning of industrial development in the Arctic. This new information may support Indigenous Peoples, governments and stakeholders to align their decision-making with the Sustainable Development Goals in the Arctic,” says Prof. Schaepman-Strub.

Julia Hager, Polar Journal AG