What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic.

Rapid global warming, extractive capitalism, threats to wildlife, ecotourism, indigenous rights disputes, even a bit of international friction—it’s all happening above roughly 66° 34′ north latitude—aka the Arctic Circle. Four million people live up there, along with polar bears and reindeer, and what happens there impacts all of us.

Next semester two College of Arts & Sciences classes will examine life in the icy north.

Arctic Studies, CAS AM 501, taught by Adriana Craciun, a CAS professor of English and holder of the Emma MacLachlan Metcalf Chair in the Humanities, “immerses students in the dynamic world of the circumpolar Arctic,” according to the course description, with a focus on the North American and Scandinavian sections.

Peoples of the Arctic, CAS AR291/AN291, taught by Catherine West, a CAS research associate professor of archaeology and of anthropology, will look at the “diverse and thriving communities” of the region, using archaeological, oral history, historic, and ethnographic data, exploring how the past can be used to highlight contemporary issues in the region. (Both courses fill departmental and BU Hub requirements.)

“Everyone is connected to the Arctic,” Craciun says.

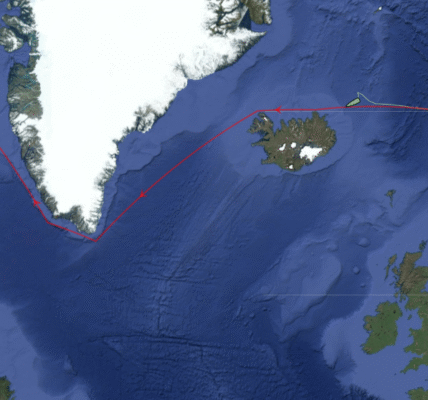

She should know. She’s been there several times for her research, most recently this fall when she traveled to Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago above the Arctic Circle. As she puts it: go to the top of Norway and turn right.

“It was terra nullius for a very long time, until the 1920s,” she says. “That meant it had no native population. So anyone in the world could basically go out there and start mining or hunting or whatever. So it was this international, very Wild West kind of frontier place.”

The Svalbard Treaty went into effect in 1925 and made the archipelago part of Norway, but with unusual provisions, so that any nation that signs the treaty (even today) can establish a scientific base there or conduct business. “Now there is intensifying international attention because of climate change,” Craciun says, with a significant Russian presence as well as scientists from many nations. Things have been a little less neighborly up there since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, she notes.

Temperatures in Svalbard in October reached 15 to 20 degrees Fahrenheit—“unusually warm,” Craciun says. She stayed in the largest town in the archipelago, Longyearbyen, on the coast of the island of Spitsbergen, where there are some nice small hotels and restaurants and cruise ships stop. But it’s not Comm Ave.

“The famous thing people say about it is that it has more polar bears than people, which is true,” she says. “You can’t leave town without an armed bear guide.”

You may have heard of the Norway-owned Svalbard Global Seed Vault, on the island of Spitsbergen, which holds more than 1.2 million seed samples as a genetic backup for biodiversity and the world’s food supply in case of global catastrophe. Beyond the doomsday-bunker entrance is a subterranean vault, buried inside a mountain under permafrost and rock, in which the seeds are frozen at -18°C.

The vault is opened only three times a year, when it takes deposits of seeds from all over the world. On a previous visit during a deposit week, Craciun was able to go inside with vault scientists, but after some flooding a few years ago, access has been even more restricted. So in October, she met with the director and other scientists in Svalbard, as well as visiting the vault’s headquarters in Sweden.

State of “immortality”

Craciun is writing a book about how scientists and ordinary people have been fascinated by the abilities of plants and seeds to survive for extreme periods of time, longer than the lives of individual humans and even of civilizations, potentially reaching a state labeled as “immortality.” Her project focuses on the Svalbard Global Seed Vault as our own current iteration of this much older scientific and humanistic project, reaching back to the Scientific Revolution.

Scientists in the 1700s and 1800s devised experiments to explore the limits of seed longevity, but their scientific interest was always inseparable from a larger cultural and specifically religious inquiry into the mysterious powers of seeds to remain dormant and awaken, with a socially meaningful and often religious component.

“Seeing the Seed Vault as part of this much older Enlightenment tradition, not just as a creature of 20th-century genetic resource research or our climate crisis,” she says, “is crucial if we are to understand” the intense public focus and attachment to it.

The class, however, will take a wider, interdisciplinary look at the region, she says.

“I’m hoping people will be interested, in that there’s a geopolitical dimension, there’s a historical, anthropological dimension to the Arctic as a whole,” she says. A lot of the class will focus on the North American, Arctic, and the pan-Arctic Inuit culture, including literature, songs and poems, art, and films by young Inuit filmmakers.

Craciun also organizes the Arctic Environmental Humanities Workshop Series for the Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future and the Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge. The series’ next virtual symposium is December 12. (Find details below.)

Normally when you read about the Arctic in the news, she says, it’s always about sea ice loss or another bad climate change milestone. “It is warming faster, at least four times faster than the rest of the world, which is just a number. But when you go there, it’s so apparent, the changes are happening so quickly.

“But it’s not just a climate lab for us here in the south to worry about or to think about. It’s important to populate it with histories and layers of meaning and multiple kinds of living beings.”

A rarified, mystical place?

That’s also the goal of West, whose Peoples of the Arctic class will teach students to look beyond the common images of the Arctic as either a wasteland or a rarified, mystical place.

“In fact, it’s got this deep human history, people are well adapted to live there, people still thrive there today,” West says. “It is a space that has a deep, deep indigenous history. And we’re also going to look at its paleoenvironmental records, what did it look like 40,000 years ago, 10,000 years ago, 1,000 years ago, when there were huge changes in climate.”

The class will also examine cultural change through the Alutiiq people of the Kodiak Archipelago, who’ve lived there for almost 8,000 years, and their salmon fishery; whaling along the North Slope of Alaska, its cultural and biological significance; and places in Greenland where the archaeological record is being seriously threatened by rising sea levels, literally crumbling into the ocean.

It’s [the Arctic] not just a climate lab for us here in the south to worry about or to think about.Adriana Craciun

“Indigenous people have suffered terribly under colonization and climate change threats and industrialization,” West says. “And yet they continue to thrive and adapt.”

She also wants her students to understand the diversity of evidence used to understand this long trajectory, including historical documents, oral history, and archaeological evidence, like artifacts and bones and plants.

West’s research now focuses on how these animal bones and their reflection of the local environment can be used to inform contemporary environmental questions. So how has warming or cooling affected specific animal species like Pacific cod and Pacific salmon, which today are struggling as marine heat waves increase in frequency in the Gulf of Alaska and here in the Gulf of Maine?

“It’s pretty straightforward to connect these long-term records to contemporary questions,” she says.

The environment has been part of West’s connection to the Arctic from the beginning. She first visited the far north when one of her professors in college got funding to excavate sites in the Aleutian Islands after the Exxon Valdez oil spill and asked if any students wanted to join the monthlong summer dig.

“I thought, this is pretty fun. I want to do this again,” she says.

The latest event in the Arctic Environmental Humanities Workshop Series is a virtual symposium, Svalbard: Four Times Faster, an interdisciplinary conversation exploring the social, geopolitical, and cultural forces transforming this unique and cosmopolitan place in the face of climate change. It will be held Tuesday, December 12, from 9 to 10:30 am, and is free and open to the public. Register here.