With more ships venturing across the Arctic, especially in marginal conditions during winter and spring, Polar Code rules may have to be expanded, a new report suggests. Shipping experts also caution that Russia may not be enforcing the existing rules as it sends a growing number of vessels through its Arctic waters.

A new study on Arctic shipping uses satellite tracking data (AIS) and meteorological data from across the region to assess the effectiveness of the Polar Code – The International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters – at mitigating maritime risks.

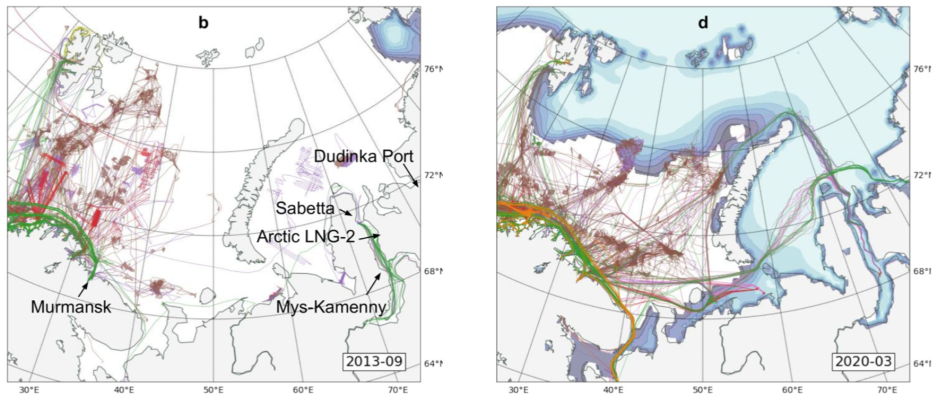

The researchers used data from 2013-2022 to identify to what degree and where vessels were exposed to hazardous weather and sea conditions while traveling across the Arctic Ocean.

The report concludes that the current Polar Code, which took effect in 2017, may contain gaps in its definition of hazardous conditions, especially in the face of the rapid increase in shipping traffic.

Year-round shipping

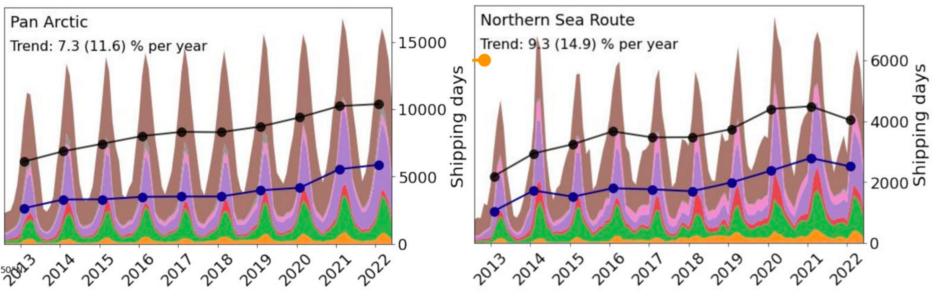

Over the past decade the number of Arctic shipping days (excluding fishing vessels) has increased by 12 percent annually.

The growth has been most pronounced in the Russian portion of the Arctic along the Northern Sea Route (NSR), in West Greenland, and in the Chukchi-Bering Sea corridor. Norway’s Svalbard area has also seen an increase in shipping traffic, though with higher annual variability, in part due to reduced cruiseship traffic during the pandemic years.

Across the Arctic the researchers were able to observe a trend away from seasonal and toward year-round shipping activity.

Between 2013 and 2022 the number of shipping days during winter and spring, when the most severe ice conditions are encountered, increased from around 2000 days to 5000 days. During this time period winter-spring traffic along NSR tripled from roughly 500 days to more than 1500 days.

In order to develop an accurate picture of the weather and sea conditions vessels faced, the study overlayed shipping data with the locally prevailing temperature and sea ice conditions.

Using this method allowed the researchers to identify the number of days ships spent in “close ice” conditions, with ice concentrations above 80 percent.

Across an entire year the number of ship days in close ice increased from 150 per month to 500 per month. The change was most pronounced during the winter months, when monthly figures quadrupled between 2013-2022 to more than a 1000 ship days.

A large share of this increase is the result of expanded navigation season along the NSR, especially by LNG carriers and crude oil & product tankers.

“The increase in shipping activities in the sea-ice-infested NSR can be attributed to the strong increase in winter-spring season activities,” the researchers conclude.

Beyond ice extent and temperature

In addition to sea ice extent, the study also looked at the geographical distribution of low air temperatures in relation to shipping activity, noting a similar increase in “annual exposure” to low temperatures from around 200 ship days to between 500-800 days during the winter months.

Currently the Polar Code uses sea ice conditions and low temperatures to assess the risk to vessels in the Arctic.

However, the study suggests, shipping traffic also faces challenges from wind, waves, visibility and the combination of air and ocean conditions, which can for example result in freezing spray. It is especially this kind of vessel icing that can represent a significant hazard and resulted in previous capsizings.

These additional metrics should be included in the Polar Code and should be considered when classifying what conditions vessels are expected to encounter.

Further recommendations relate to requiring the use of more localized and up-to-date information of weather and sea ice condition, rather than utilizing historical patterns or averages.

Will the tankers comply with the Polar Code?Hervé Baudu, Chief Professor of Maritime Education at the French Maritime Academy

The study suggests that this type of real-time data is available e.g. from the Worldwide Met-Ocean Information and Warning Service, and its use should be made mandatory.

New rules or enforcing existing rules

The paper did not discuss issues related to vessels’ compliance with the Polar Code. With recent shipments of crude oil on aging non-ice class oil tankers, experts have repeatedly raised concerns that it is doubtful that Russia enforces the Polar Code for all vessels traveling along its NSR.

“Will the tankers comply with the Polar Code? This is doubtful,” concluded Hervé Baudu, Chief Professor of Maritime Education at the French Maritime Academy (ENSM), during a previous interview with HNN.

In new comments he added: “The NSR administration is not qualified to ensure that the tanker meets all the requirements of the Polar Code to make the crossing. When a vessel submits its application for authorization to cross, Northern Sea Route Administration (NSRA) regulations do not check whether the vessel is in compliance with the Polar Code (nor is it its role to do so).”

For Russia the desire to quickly increase and normalize traffic along the route could certainly trump concerns over regulations, at least during the summer navigation period. The use of a fleet of “gray” poorly ensured vessels carrying oil further increases the risk.

“We could therefore expect ships to transit along the NSR solely at the whim of the Russian authority, which is very keen to advertise the increase in traffic on the transit route,” Baudu concludes.

Dr Sian Prior, Lead Advisor to the Clean Arctic Alliance, an environmental advocacy group, echoes a similar need to enforce existing rules.

“International regulations to improve the safety of shipping in the polar regions must be applied with the utmost stringency, whatever cargoes are being shipped on the Northern Sea Route,” Prior explains.

The need to apply and enforce existing regulations across all Polar regions may thus for now supersede calls to further expand rules.