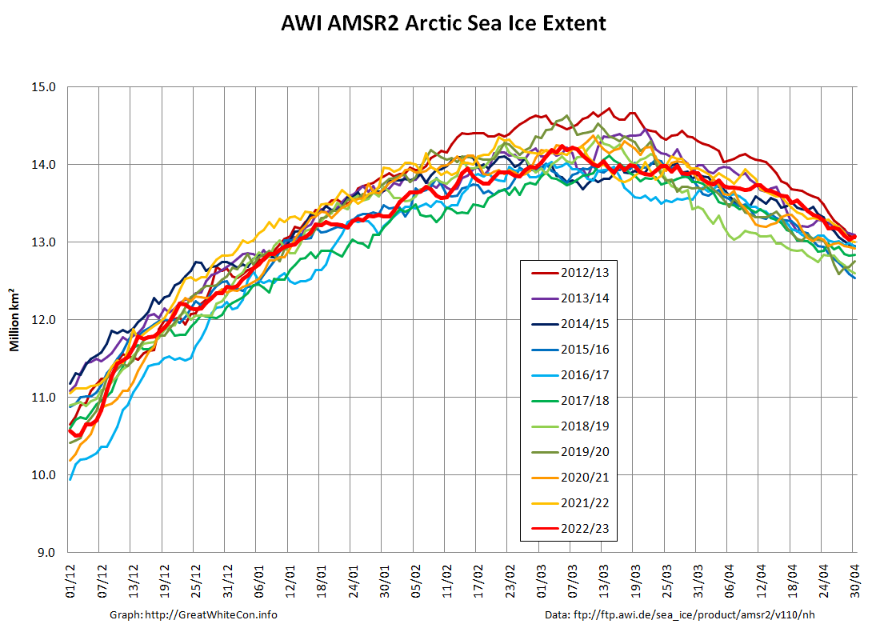

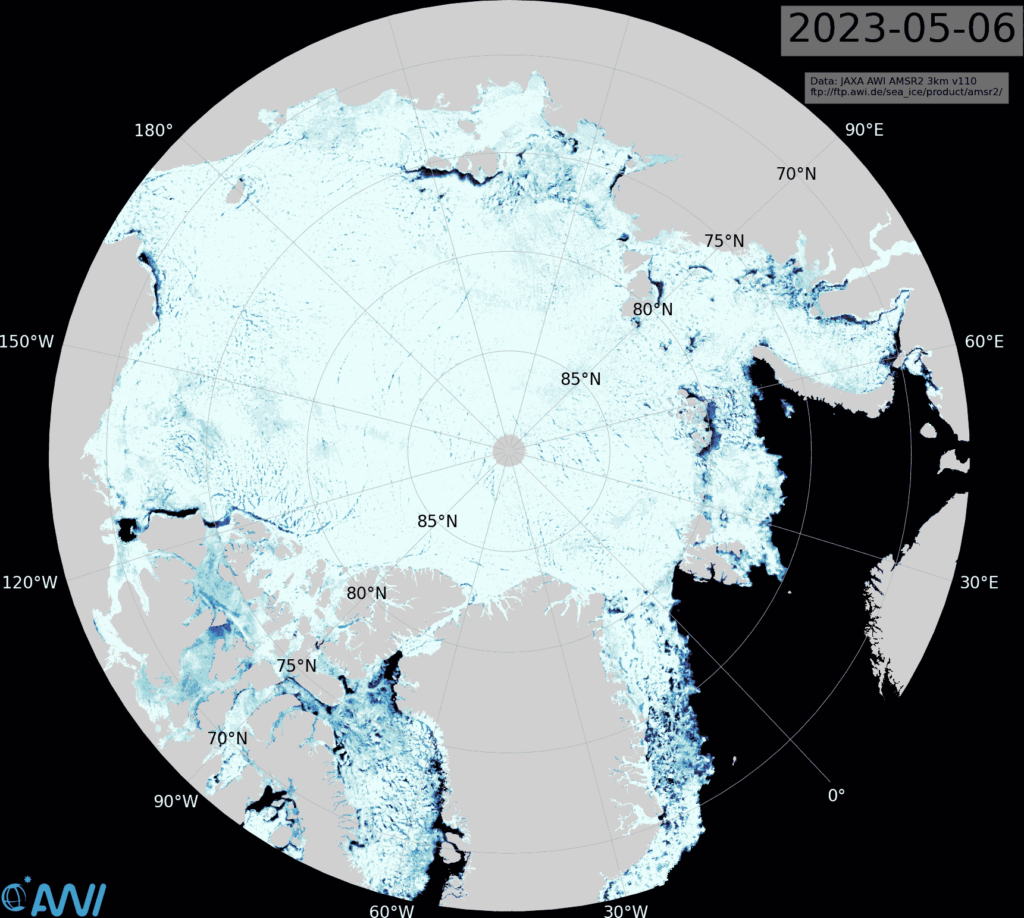

At the beginning of May AWI’s high resolution AMSR2 extent metric is at the top of the historical range:

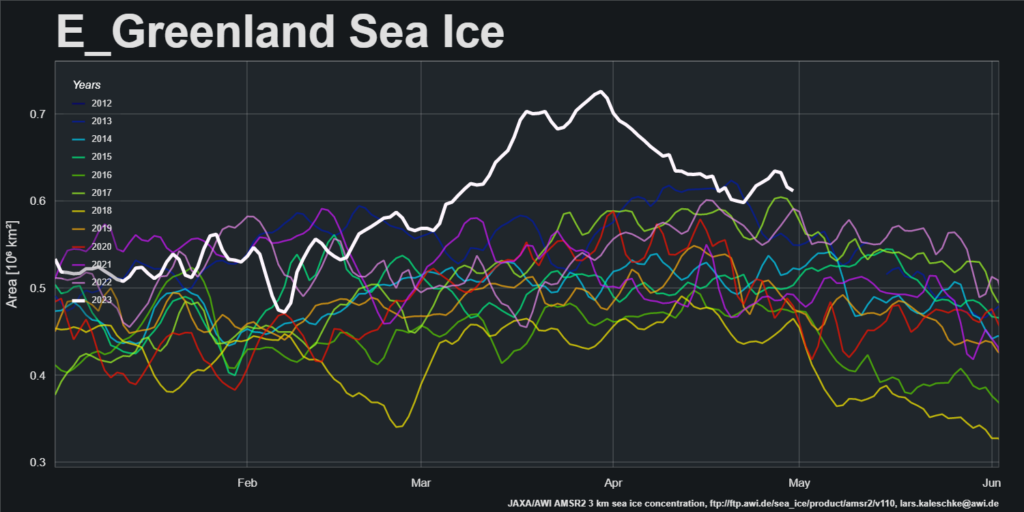

After a period of melt in the East Greenland Sea, export of sea ice from the Central Arctic via the Fram Strait has increased recently:

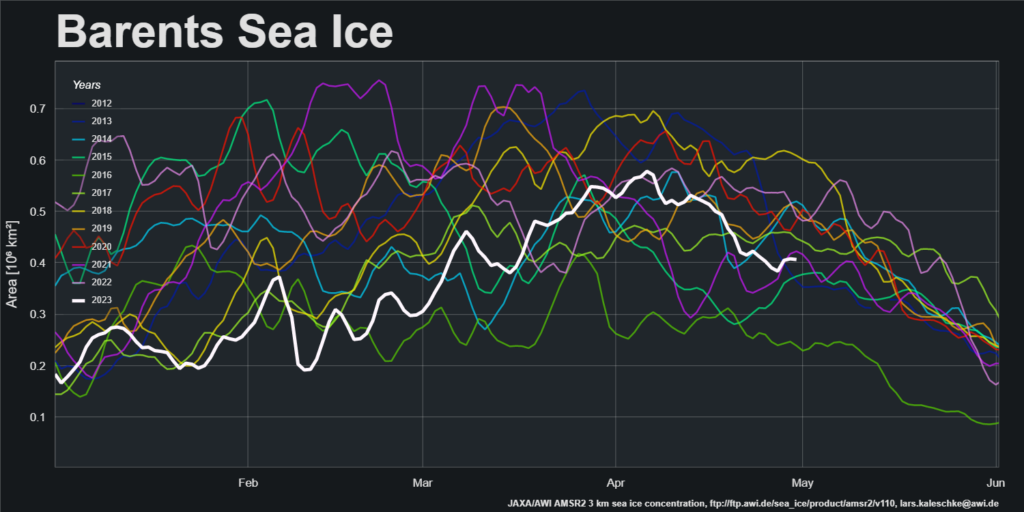

Sea ice area in the Barents Sea peaked in the first week of April and has declined steadily since then:

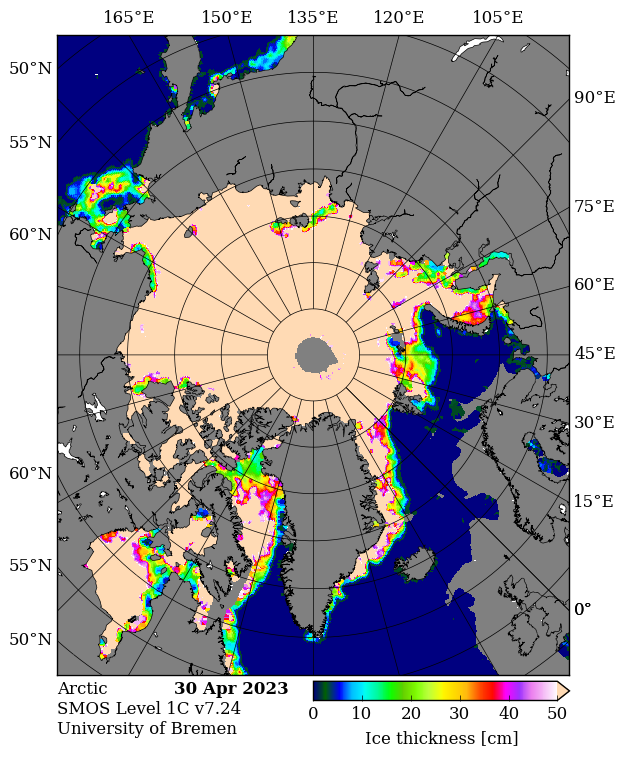

SMOS data is flowing again, and the gaps have been filled. Here’s the final pre melt ponding map of the spring:

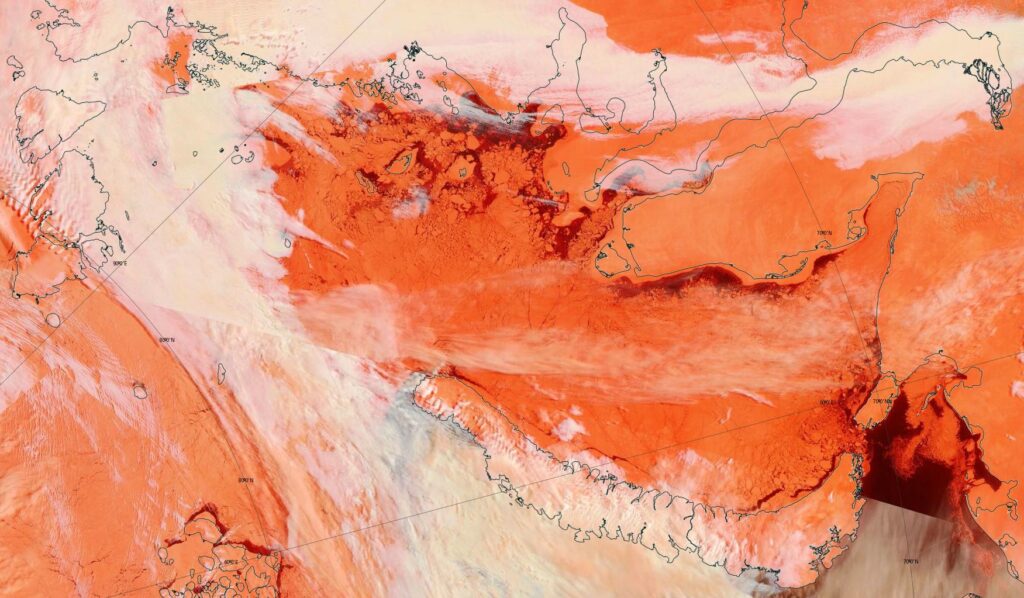

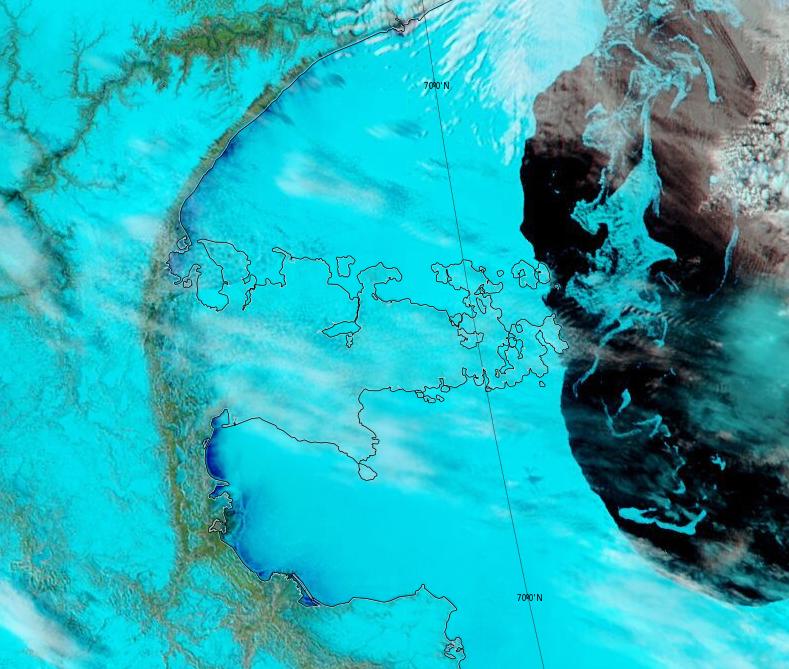

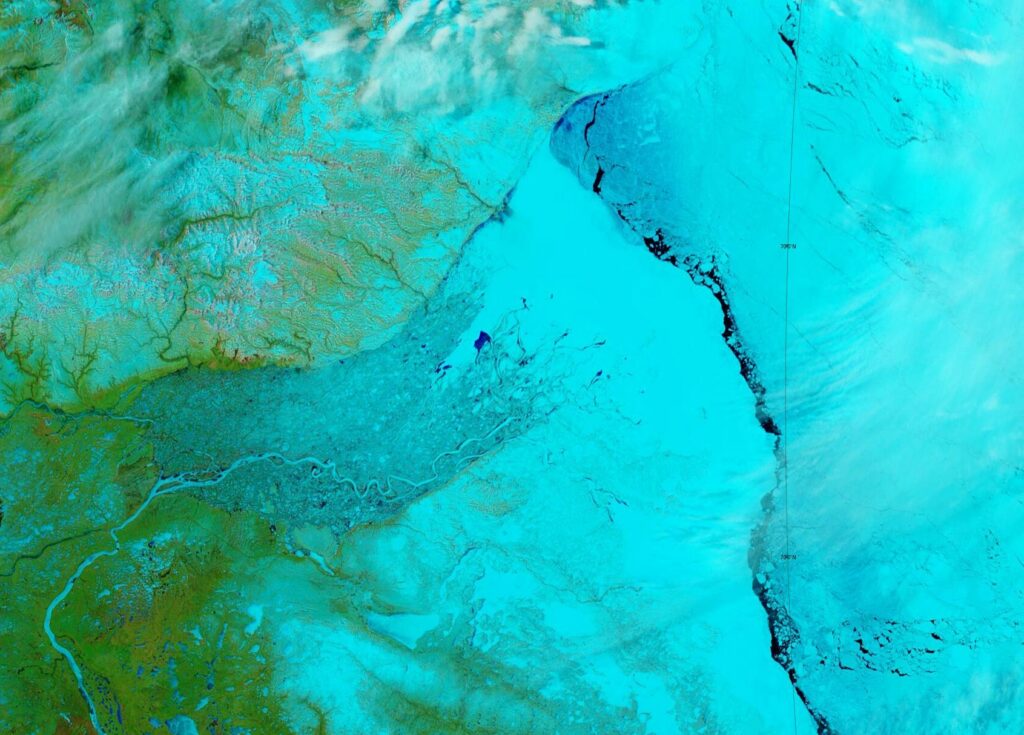

It reveals large areas of thin ice that have recently developed in the Kara Sea. Here’s a pseudo colour glimpse of the region through the clouds:

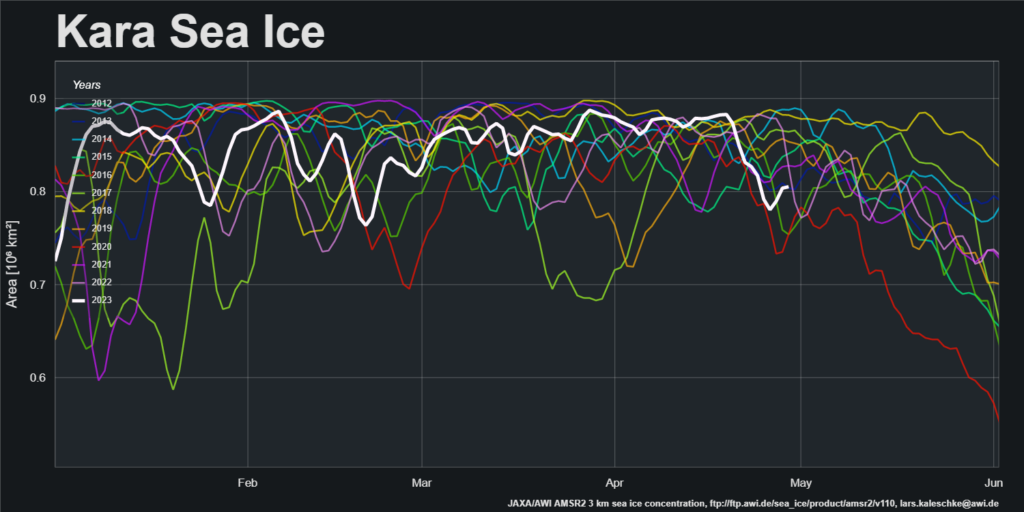

and the regional sea ice area graph:

An area of thin ice has also developed off the Chukchi Sea coast of Alaska.

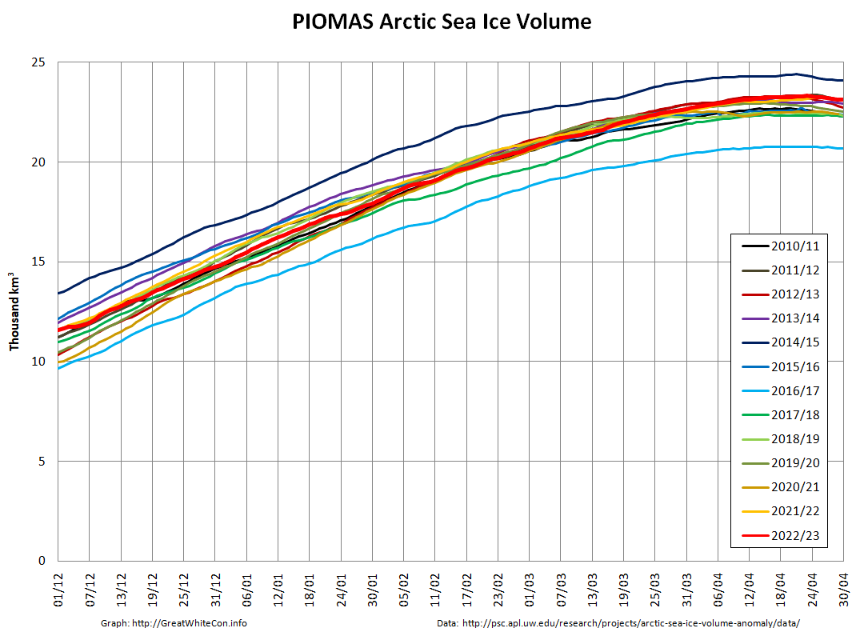

The PIOMAS gridded thickness data for April show that the 2023 maximum volume of 23,320 km3 was reached on April 23rd:

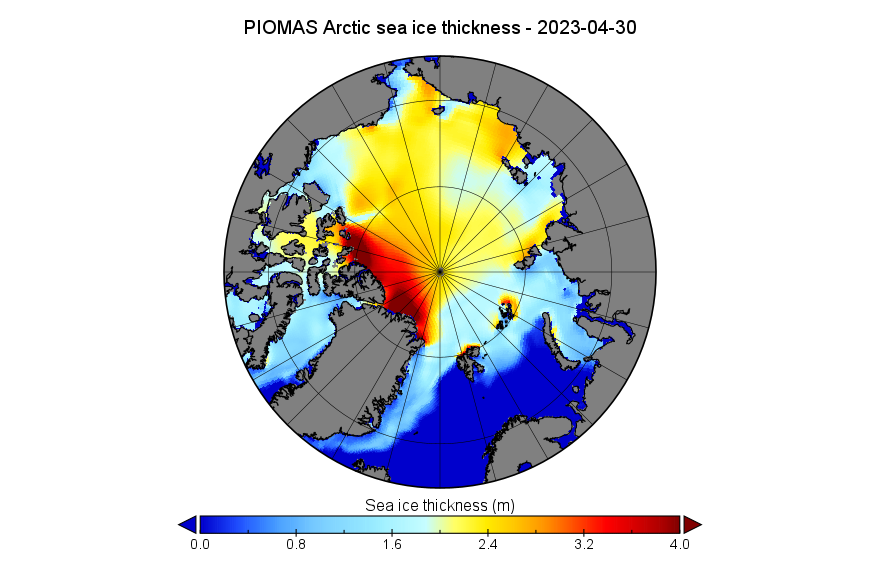

Here too is the thickness map for April 30th:

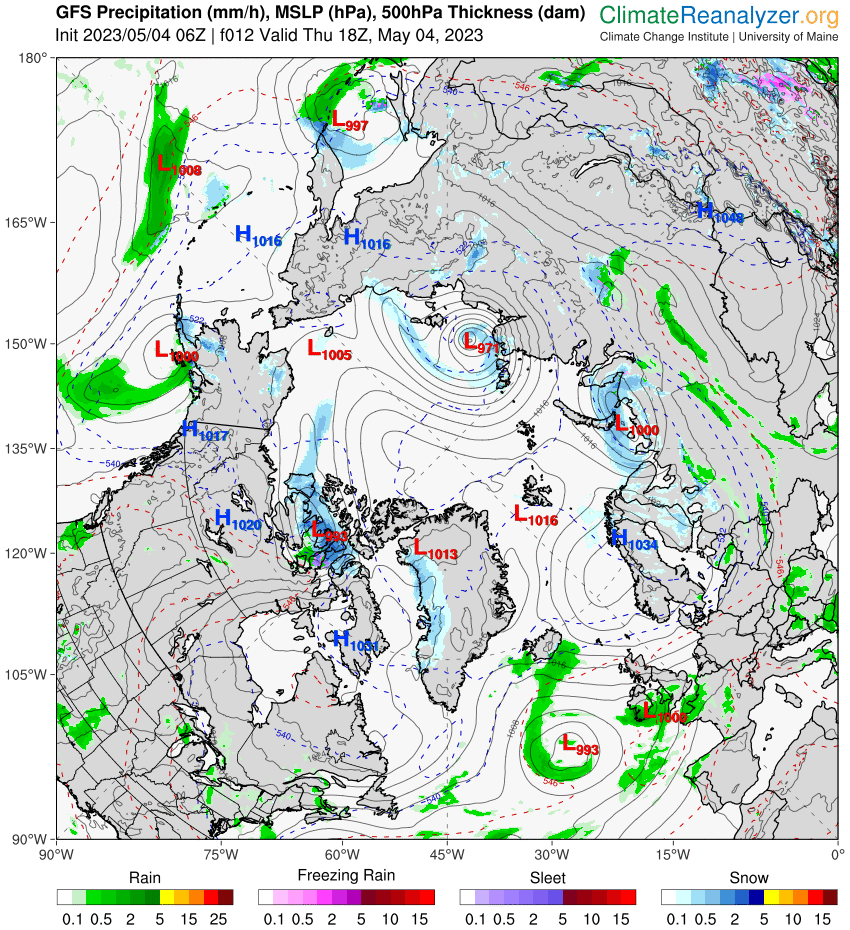

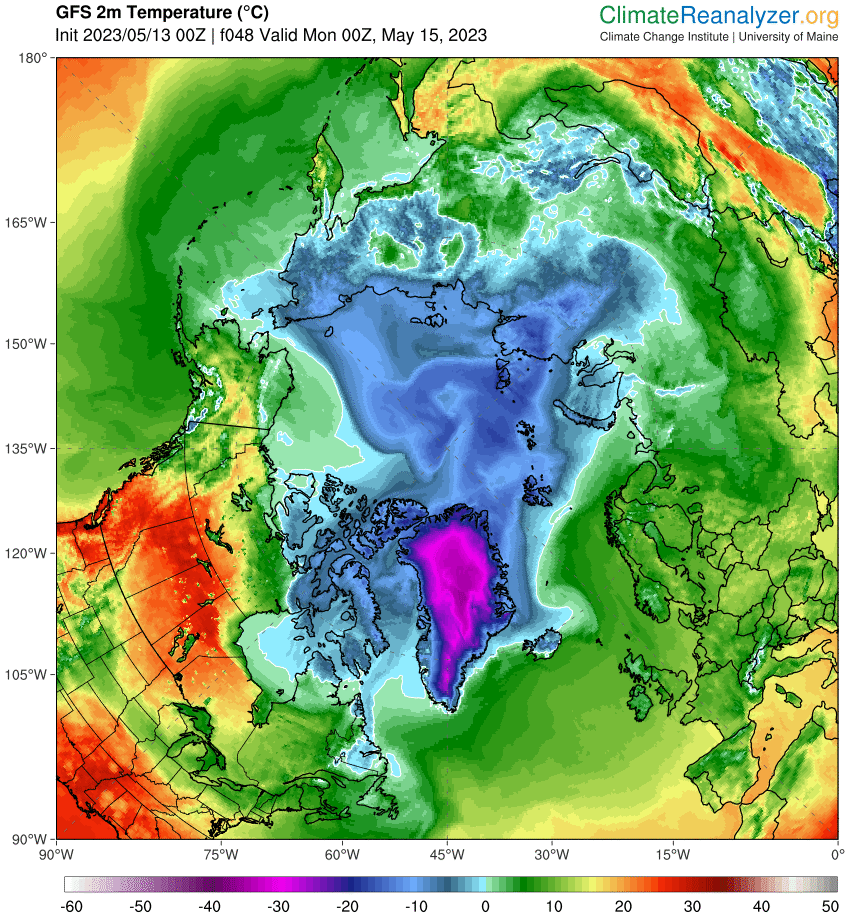

In Arctic weather news there is currently a cyclone spinning over the Laptev Sea which is forecast by GFS to reach a minimum MSLP of 971 hPa later today:

It remains to be seen what effect the inclement weather has on the ice in the region.

As Neil points out below, the May edition of the NSIDC’s Arctic Sea Ice News has been published:

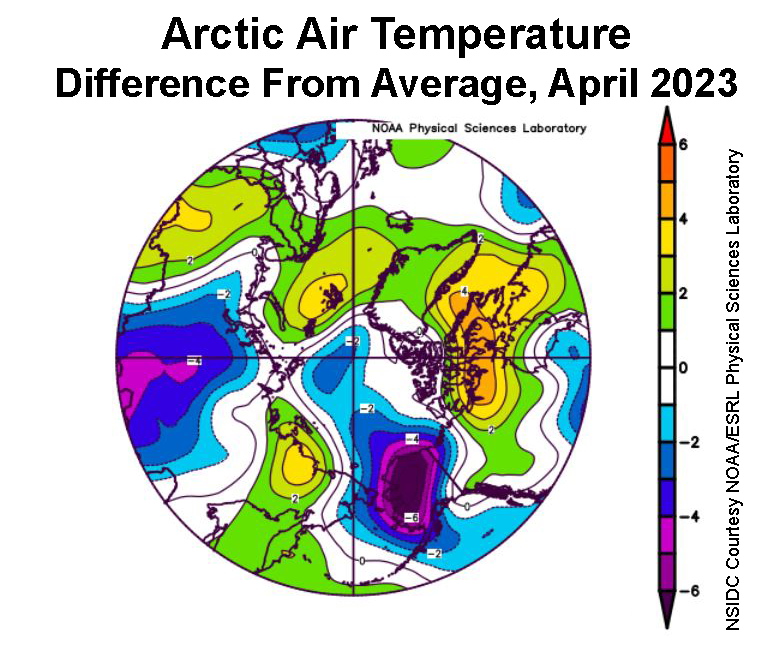

Air temperatures at the 925 hPa level in April were near average to below average over most of the Arctic Ocean. This helps to explain the slow rate of sea ice loss during April. While temperatures were modestly above average over the Barents Sea, these areas are already largely free of sea ice:

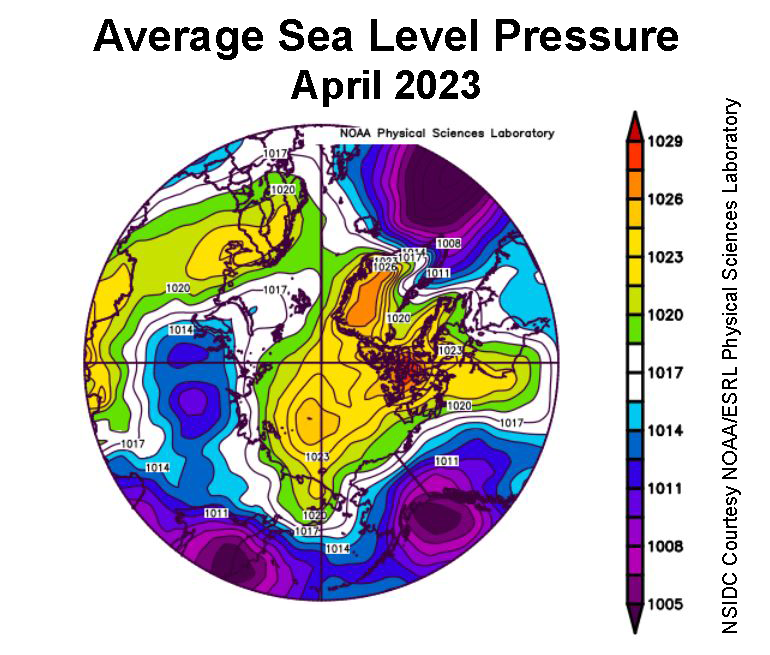

The sea level pressure pattern was characterized by fairly high pressure over most of the Arctic Ocean. The clockwise winds around a separate high-pressure center over Scandinavia brought warm winds from the south over the Barents Sea, consistent with the above air average temperatures in that area. Similarly, below-average temperatures over Alaska were driven by the combination of a strong low pressure area in the Gulf of Alaska and high pressure in the Beaufort Sea, driving air generally southward from the ice-covered Arctic Ocean.

The NSIDC article also mentions a new open access paper by Sledd et al. entitled “Clouds Increasingly Influence Arctic Sea Surface Temperatures as CO2 Rises“. Here’s an extract from the abstract:

Under pre-industrial CO2 concentrations, summer clouds have little direct effect on maximum annual sea surface temperatures (SST). When CO2 concentrations increase, sea ice retreats earlier, allowing more solar radiation to warm the ocean. Clouds can counteract this summer warming by reflecting solar radiation back to space. Consequently, clouds explain up to 13% more variability in maximum annual SST under modern-day CO2 concentrations. Maximum annual SST are three times more sensitive to summer clouds when CO2 concentrations are four times pre-industrial levels.

Since Neil is wondering about the recent “slow melt”, here’s an animation of Arctic sea ice drift over the last month. Click the image if your bandwidth supports viewing a 13 Mb video:

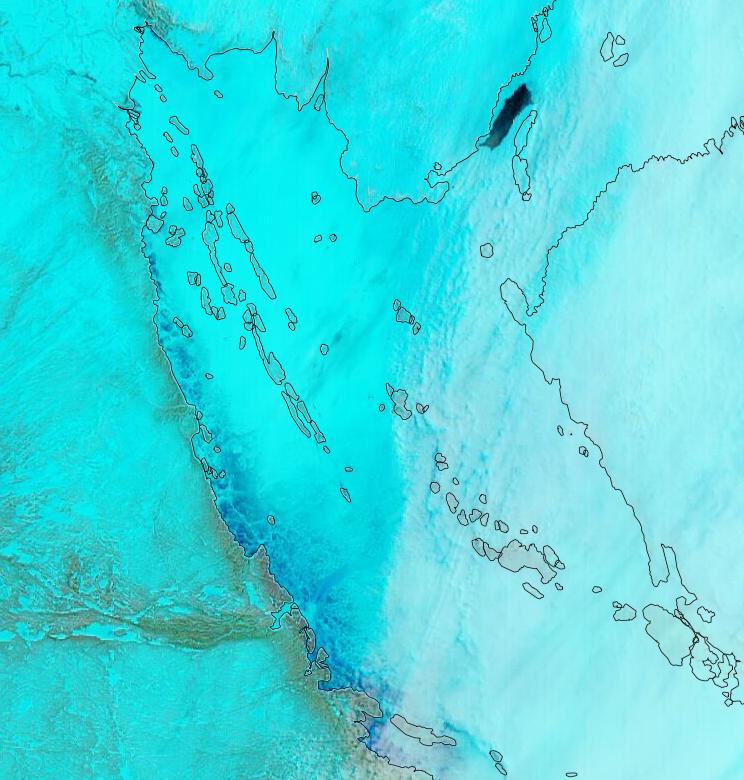

Melt ponds (and a patch of open water) are now clearly visible along the coast of the Coronation Gulf in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago:

The Swedish icebreaker Oden is now in the marginal ice zone west of Svalbard. It won’t come as a surprise to regular readers that the Art of Melt 2023 expedition blog reports that:

We encountered the first ice on the first day, which quickly became quite challenging to break, even for Oden, as there were many ridges and bumps on the ice.

Above zero temperatures are forecast for the Beaufort Sea by the end of the weekend:

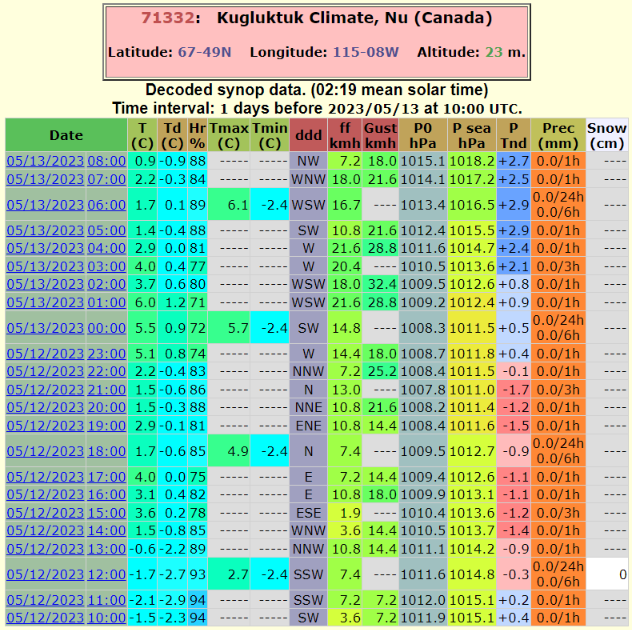

The weather is already warm in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Here’s the report from Kugluktuk for the last 24 hours:

Melt ponds are now visible in Franklin and Darnley Bays:

Melt ponds are now visible in the Beaufort Sea off the Mackenzie Delta:

Watch this space!