For nearly three decades, the Arctic Council has been a successful example of post-Cold War cooperation.

Its eight members, including Russia and the United States, have cooperated on climate-change research and social development across the ecologically sensitive region.

Now, a year after council members stopped working with Russia following its invasion of Ukraine and as Norway prepares to assume the chairmanship from Moscow on May 11, experts are asking whether the polar body’s viability is at risk if it cannot cooperate with the country that controls over half of the Arctic coastline.

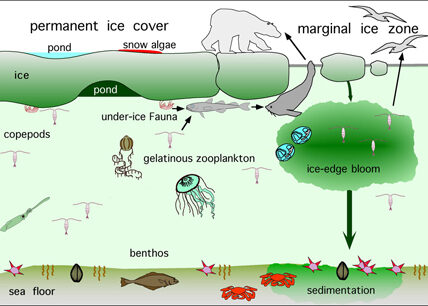

An ineffective Arctic Council could have dire implications for the region’s environment and its 4 million inhabitants who face the effects of melting sea ice and the interest of non-Arctic countries in the region’s mostly untapped mineral resources.

The work of the council, which comprises the eight Arctic states of Finland, Norway, Iceland, Sweden, Russia, Denmark, Canada and the United States, in the past has produced binding agreements on environmental protection and preservation.

It is also a rare platform giving a voice to the region’s Indigenous peoples. It does not deal with security issues.

But with the end of cooperation with Moscow, about a third of the council’s 130 projects are on hold, new projects cannot go ahead and existing ones cannot be renewed. Western and Russian scientists no longer share climate change findings, for example, and cooperation for possible search-and-rescue missions or oil spills has stopped.

“I am worried that this will really hobble the ability of the Arctic Council to work through these various issues,” U.S. senator Angus King from Maine told Reuters.

A DIVIDED REGION?

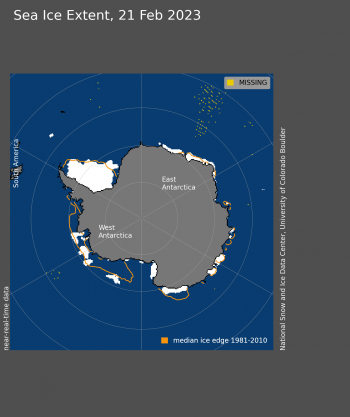

The Arctic is warming about four times as fast as the rest of the world.

As sea ice vanishes, polar waters are opening to shipping and other industries eager to exploit the region’s bounty of natural resources, including oil, gas, and metals such as gold, iron and rare earths.

The discord between Russia and the other Arctic Council members means that an effective response to these changes is far less likely.

“Norway has a big challenge,” said John Holdren, co-director of the Harvard Kennedy School’s Arctic Initiative and a former science advisor to U.S. President Barack Obama. “That’s how to rescue as much as possible of the Arctic Council’s good work in the absence of Russia.”

Russia argues this work cannot continue without it.

The council is weakening, Russian Arctic Ambassador Nikolay Korchunov told Reuters, saying he was not confident it “will be able to remain the main platform on Arctic issues”.

Adding to the worries is the possibility that Russia will go its own way on issues affecting the region or even establish a rival council.

Recently, it has taken steps to expand cooperation in the Arctic with non-Arctic states. On April 24, Russia and China signed a memorandum establishing cooperation between the countries’ coast guards in the Arctic.

Days earlier, on April 14, Russia invited China, India, Brazil and South Africa – the BRICS – to conduct research at its settlement on Svalbard, an Arctic archipelago under Norwegian sovereignty where other countries can operate under a 1920 Treaty.

“Russia is seeking to build relationships with some non-Arctic countries, particularly China, and that is a development that is concerning,” said David Balton, executive director of the Arctic Steering Committee at the White House.

Russia’s Korchunov said Moscow welcomed non-Arctic states in the region, provided they did not come with a military agenda.

“Our focus on a purely peaceful format of partnership also reflects the need of development of scientific and economic cooperation with non-Arctic countries,” he said.

HOW TO ENGAGE WITH MOSCOW

Norway says it is “optimistic” a seamless transition of the chairmanship from Russia can be achieved as it is in the interest of all Arctic states to maintain the Arctic Council.

“We need to safeguard the Arctic Council as the most important international forum for Arctic cooperation and make sure it survives,” Norwegian Deputy Foreign Minister Eivind Vad Petersson told Reuters.

That will not be easy, given Oslo’s own strained relations with Moscow. In April, Oslo expelled 15 Russian diplomats saying they were spies. Moscow denied the accusations and Korchunov said the expulsions undermined the trust needed for cooperation.

Analysts say NATO-member Norway, which shares an Arctic border with Russia, is still well-placed to handle the delicate balancing act with Moscow.

“Norway has been the most outspoken when it comes to the possibility of keeping the door ajar so that Russia could, when politically feasible, be part of the Arctic Council again,” said Svein Vigeland Rottem, a senior researcher in Arctic governance and security at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute in Oslo.

Indeed, said lawmaker Aaja Chemnitz Larsen, the council will eventually need to reengage with Russia even if that moment has not yet arrived.

“I don’t see an Arctic Council without Russia in the future,” said Larsen, a Greenland lawmaker at the Danish Parliament and the Chair of Arctic Parliamentarians, a body including MPs from across the Arctic countries.

“We need to be prepared for a different time when the war (in Ukraine) one day will be over.”