This is the second in a series of articles looking at how climate change and geopolitics are reshaping the High North’s strategic landscape, from the quest for oil and gas and mineral resources to the military balance of power.

There’s an ocean of oil and gas frozen in place beneath the Arctic. The cascading impact of climate change would argue for leaving it there. Yet the melting of the High North’s icy barriers also feeds the ambitions of nations near and far to exploit it. Countless headlines herald a new scramble for the Arctic’s hydrocarbon riches.

It’s time for a reality check. As one oilman put it to me recently in Alaska, Arctic oil production “is the closest thing to drilling on the moon.”

The moon, with politics thrown in, one might add.

The decision to drill is usually, at heart, an economic one. But the Arctic’s riches also sit atop several grinding fault lines: between development and conservation; between the rivalries of great powers and the partisan scuffles of national politics; between the local and the planetary; between fear and greed. As much as expense and physical risk, these underlying frictions determine whether or when those frozen barrels see the light of day.

Which brings us to the booms and busts of Alaska. The state has huge potential resources, but its heyday was a generation ago. A revival of sorts is happening now: The White House recently approved ConocoPhillips’ Willow project, a new oil field in the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska, angering environmentalists but pleasing state leaders and delegates on both sides of the red-blue divide. Oil production there should begin rising again after three decades of decline.

Given President Joe Biden’s green agenda, it certainly wasn’t melting ice that convinced him of Willow’s merits. Rather, after his administration drained the Strategic Petroleum Reserve last year to blunt the spike in pump prices caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it would have been bizarre, in political terms at least, to block a high-profile domestic source of oil. That Representative Mary Peltola — Alaska’s sole congressperson, and a Democrat and Native Alaskan to boot — supported Willow also provided a reason and some welcome cover.

History suggests that such political imperatives are both decisive and salutary. Yes, the broader threat of climate change dictates decarbonization. But unless the need for energy security and, importantly, local economic security are appropriately weighted in the political balance, the scales of public opinion may tip against a successful transition to a carbon-neutral future.

Unbridled Arctic drilling would be disastrous. It’s also unlikely in a place replete with natural bridles. But as much as those outside the Arctic often seem to regard it as an empty wilderness or national park, for many of those who call the region home, industrialization is an established and vital fact of life. That includes the mining of raw materials needed for the manufacture of clean energy technologies. The growing challenge that the US thus faces is not whether to tap Alaska’s resources, but how to do so in a manner that reconciles its strategic, local and environmental interests.

Ground zero is the North Slope.

A Frozen Ocean of Oil

Kuparuk is the Alaskan oil field you’ve never heard of. It lies 40 miles west and very much in the shadow of Prudhoe Bay, the single-largest oil field ever found in the US. Yet Kuparuk is no minnow: Operated by ConocoPhillips, the largest producer in Alaska, it’s the second-largest, certainly in conventional terms, covering an area rivaling that of New York City.

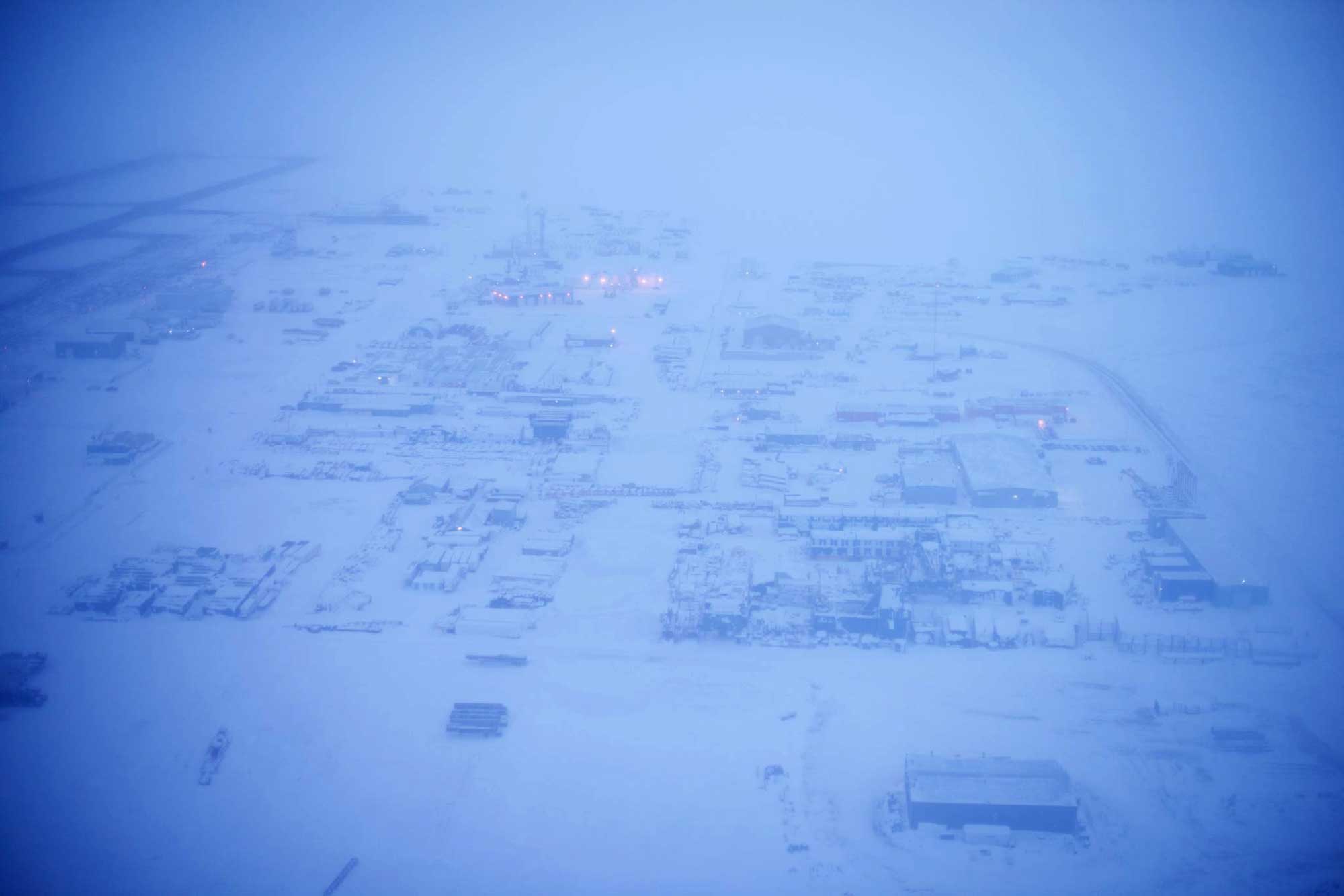

Approached from the air, Kuparuk’s operations camp and central processing facility appear as a squared-off patch of black and orange — officially, “chili pepper red” — buildings, dominated by a 192-foot rig. It’s an outpost in a flat, treeless landscape sprung from somewhere between Tolkien and John Carpenter’s The Thing. Despite the relatively mild May weather, snow and ice dominate, dotted by open patches of dun tundra and strange polygonal pools. Not far to the north, the Arctic coastline remains resolutely ice-locked.

That morning, before I took off from Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport, named for the senator who championed the state’s oil development, the check-in attendant informed me (much to her colleagues’ amusement) that the North Slope is “just like Disneyland!” The twin-engine turboprop was filled with Conoco employees and contractors, some for day trips and others to begin a typical two-week stint on the rigs. Coffee’s popular on the early morning flight; the menu lists alcoholic drinks — but only for when you’re flying back south. (Non-roughnecks, take note: Beer and whiskey are named by brand; vodka, rum and wine are generic.) For the regulars flying past Denali and then across the wide expanse of the Brooks Range, where the trees end and the Arctic North Slope begins, this is surely one of the world’s more epic two-hour commutes.

Kuparuk is an aged giant. Discovered in 1969, it started producing in 1981, peaked at more than 320,000 barrels a day in the early 1990s, and now pumps roughly a sixth of that. Whereas Alaska alone produced more than 3% of the world’s oil supply at its 1980s peak, today the entire Arctic produces a smaller share than that. Russia is the Arctic whale, accounting for 90% of current production, including natural gas.

Russia also dominates when it comes to the biggest Arctic projects either producing already or in the pipeline. (With estimated reserves of 600 million barrels, Willow doesn’t even make the top 10.)

Things get more nuanced when it comes to resources, though. An oft-cited US Geological Survey from 2008 called the Arctic the “largest unexplored prospective area for petroleum remaining on Earth,” with a mean estimate of 412 billion barrels of oil equivalent of crude, other liquids and natural gas. If only a tenth of that could be extracted, it would be far bigger than the proved reserves of Brazil.

This is where Alaska punches above its geographic weight: Its crude oil resources were estimated to be bigger than that of the entire arc of Russian territory curving around the pole. Russia is more of a gas giant there.

Educated guesses, and old ones at that, to be sure. They are big numbers, though, and politicians, generals and, of course, oil companies around the world cannot help but wonder if they might be realized — and by whom.

Empire of Gravel

If oil is the prize, the rostrum is made of another vital, if less storied, commodity: gravel. Arctic industrialization is built on stone chips. Mimicking the geological process that formed the North Slope in the first place, oil producers mine gravel locally and deposit it to provide even platforms. A typical 12-acre pad, 4 feet thick, requires 100,000 tons. The Kuparuk road network, 155 miles of gravel ribbons linking pads and other facilities, alone cost $1 billion to construct.

In the middle of the flight north, somewhere over the Alaskan interior, I pick out two threads running in parallel across the otherwise empty landscape: the Trans-Alaska Pipeline and the Dalton Highway, or Haul Road, which begins 80 miles north of Fairbanks and runs 414 miles to Deadhorse, the North Slope’s unofficial oil capital next to Prudhoe Bay.

While the highway is open to the public these days, it makes for a daunting, or outright perilous, road trip, especially in winter. It is mostly — what else? — gravel and dirt. For those heading north, the isolated truck stop at Coldfoot is like the point of no return. It offers the last services for 240 miles before reaching Deadhorse, with the Atigun Pass (elevation: 4,739 feet) lying in between. Provided you have enough food, water, fuel, emergency supplies and maybe a satellite phone — plus a large measure of optimism or fatalism — you can drive to the North Slope. For most, though, it’s a place to land, not pull up to.

Photographer: Louie Palu/Agence VU

Photographer: Louie Palu/Agence VU

Photographer: Louie Palu/Agence VU

Photographer: Louie Palu/Agence VU

Photographer: Louie Palu/Agence VU

Coldfoot, Alaska, is one of the state’s few settlements inside the Arctic Circle that is accessible by road. Trucks stop here in the foothills of the Brooks Range, their last chance for fuel, a bite or anything else before driving the final 240-mile leg – roughly the same as Washington to New York – north on the Dalton Highway to Deadhorse.

The tree line is nature’s signal that you’ve entered the Arctic, reaching an environment too extreme to support forests. It isn’t an exact alignment: In Alaska, trees extend slightly above the Arctic Circle to the south-facing slopes of the Brooks Range, which offers shelter from cold air sweeping down from the Arctic Ocean.

The James W. Dalton Highway is named for an Alaskan engineer who supervised construction of the Distant Early Warning Line radar system, or DEW Line. The two-lane highway was built to enable construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, which it parallels, and to haul heavy equipment to the oil operations around Prudhoe Bay.

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline runs 800 miles from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez. More than half of it runs above ground in order to prevent melting of the permafrost. The pipeline is built in a zig-zag pattern to allow for thermal expansion and contraction and also for any movement from earthquakes. Almost 19 billion barrels have flowed through the pipeline since it began operating in 1977.

At the end of the highway, and the end of the earth, sits Deadhorse, an unincorporated community that serves mainly as an industrial camp and supply base for the oil fields on the North Slope. Its lowest recorded temperature, including wind chill, was negative 135 degrees F, in January 1989.

The rigors of the North Slope winter — wildly negative temperatures and 56 straight days of darkness — are real enough. But at least from an economic perspective, sheer remoteness is the defining element.

Ben Tolman, Conoco’s drilling superintendent at Kuparuk, cares more about self-sufficiency than layering up. We’re standing inside a rig near a steadily rotating drill that’s about to cross the 9,000-feet mark somewhere below the permafrost. He tells me the surrounding 50-foot-high steel walls and activity keep the temperature in the rig surprisingly constant year-round: “I wear the same thing in winter that I’m wearing now,” he says pointing to his sweater.

The bigger concern is something breaking. Tolman hails from Wyoming, where the oil fields are pretty remote for the Lower 48. Even so, he tells me, a broken tool there could be identified and a new one machined in and delivered from Texas within 24 hours. “That doesn’t happen here.” He adds: “Right now, if you can’t fit it in a C-130 [a large cargo plane], it’s not getting here until next winter,” when ice roads can be built to haul heavy equipment over land.

The ice roads themselves are feats of engineering, and ones that come with rapid obsolescence by design. For seasonal or one-off jobs, like resupply or pipeline construction, an ice road leaves the organic topside of the tundra intact, melting back into the landscape in the summer. Every winter, a 40-mile ice road system is built around the neighboring Alpine field: Four crews lay down ice chips like aggregates, cementing them with up to a million gallons of water per mile drawn from nearby lakes and then smoothing the mix into a hardened, frozen surface. Each mile takes about two to three days to build, which, compared with Manhattan construction schedules, honestly sounds amazingly quick.

Despite being on land, the oil field resembles an archipelago of islands. Kuparuk’s main operations pad is like a small, self-contained city. The need to minimize environmental impact means, despite the vast wilderness, that space is at a premium. Advances in drilling enable a 12-acre pad to tap a sub-surface area almost 20 times the size that a 65-acre pad could reach 50 years ago. More than a thousand workers can sleep, eat and work there. The operation’s fire hall, full of gleaming engines and trucks, would rival any municipal department (“There is no mutual aid for us,” says the fire chief, matter-of-factly).

The lights, and the rigs — as well as a nearby Norad radar facility — are kept running by a 115-megawatt micro-grid powered by surplus natural gas. When I visited, workers were 10 days into a painstaking three-week repair job inside one of the larger gas turbines.

When something needs fixing, “you can add zeros to the financial impact here,” says Tolman, “so you might not take the same up-risk as down south.” In keeping with that, control rooms are cockpits of automation and redundancy. Over at the neighboring Alpine field’s nerve center, two workers survey several dozen screens arranged in a towering semi-circle, a digital amphitheater visualizing 120,000 touchpoints on the system in a bewildering array of tables and diagrams. “This thing is engineered to shut down,” says one. If the automatic checks somehow fail, there’s a big red board of 44 buttons to do it manually. Pro tip in an emergency: Those buttons are really handles to be pulled, not hammered with your fist.

Redundancy and self-sufficiency equal extra cost, which doesn’t end there. There’s the in-house airline to ferry workers in and out. The oil they produce is then shipped 800 miles in the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, also part owned by Conoco, to Valdez on Alaska’s south coast, where like as not it will be loaded onto the company’s Jones Act-compliant tankers, which must be US-built, US-owned and US-crewed in order to ship between US ports.

Such autarky, however necessary, is unusual in this industry. It helps to explain why the ocean of oil isn’t frozen just by ice.

Only Big Oil Need Apply

Something that becomes clear in the Arctic is that doing anything there takes longer. That includes drilling for oil. The National Petroleum Council estimates that developing a typical onshore Alaskan discovery takes about 15 years; offshore projects might take more than three decades. Think about that: A greenfield offshore prospect leased today might not pump a barrel until the early 2050s. Meanwhile, a project in the Gulf of Mexico takes perhaps a decade; shale prospects, a handful of years or even months.

For big industrial projects, such lags can be poison. Time chisels away at the value of money. It also opens a long window in which Alaska’s shifting tax codes and America’s yo-yoing energy and climate policies can change. Shell Plc spent years, and billions, on ill-fated exploration in the Chukchi Sea off northwest Alaska before giving up in 2015. Besides other setbacks, including a wrecked rig, 2010’s Deepwater Horizon disaster some 4,000 miles away in the Gulf of Mexico ignited a political firestorm around offshore drilling, forcing Shell to change plans mid-project.

Most of Alaska’s potential oil resources are thought to lie offshore, where moratoriums imposed by former President Barack Obama and expanded by President Joe Biden — his green yin to the Willow approval’s yang — have closed off drilling. Assume those were lifted, and an oil rush still seems unlikely. The few existing projects in the shallow depths off the North Slope are literal islands of (you guessed it) gravel. Even in late May they look like tiny redoubts besieged by hordes of ice. The Northstar field, operated by Hilcorp Energy Co., took 22 years from initial leasing to commercial production.

Wildcatting may define the oil industry, but the most profitable place to drill is often where you already are — especially when where you are is as remote as this. One reason Conoco can contemplate spending $8 billion to develop Willow, discovered seven years ago and with first production not expected for another six, is that it is just 8 miles from where the company has already invested so much in pipelines, buildings, roads, gravel mines, planes, tankers and the rest of it nearby. Rystad Energy, a consultancy, estimates Willow’s net present value — the project’s overall profit after all costs in today’s money — at almost $3 billion, assuming a $65 flat oil price.

In short, only the biggest oil companies can afford to take the risks and the time to develop Arctic fields. That holds true for Russia and Norway, too, where the role of state-backed companies, enjoying de facto access to the national balance sheet, has been critical. Whereas almost 40 companies used to be in the Alaska Oil and Gas Association, a trade group, now there are just 14. That reflects not merely the decline in Alaska’s production but also the steady concentration of larger firms able to operate there. A write-off such as Shell’s Arctic misadventure would kill most companies.

Even with Conoco’s scale, three-quarters of its leased acreage on the North Slope remains undrilled, and the company expects only modest production growth in Alaska over time. In part, this represents a financial constraint: Conoco led the industry in switching away from the high spending of the shale-fueled 2010s to high payouts instead. Like other large producers, Conoco also has a global portfolio of projects that compete for its investment budget.

At one point on the rig at Kuparuk, I am struck by how few people there are relative to the scale of the operation, with 50 to 60 personnel, mostly contractors, working on any given day. The driller’s cab, with its shopworn pilot’s chair, joystick and screens, looks borrowed from the Millennium Falcon. His job is partly automated, with a software system called Novos smoothing out the inevitable inconsistencies humans introduce to any repetitive industrial process. Alaska’s oil and gas workforce has roughly halved since 2014, when triple-digit prices crashed, partly reversing decades of declining productivity. Still, I can’t help but think that the costs and risks of maintaining workers out here at the end of the earth — and minimizing their imprint — makes it a prime target for the machines. Even, or perhaps especially, in the Arctic, industrialization yields eventually to computerization.

While the Arctic has a lot of oil and gas, so do other places where it may be easier, faster and cheaper to get at. Unlike today, Texas’s production was in decline when Alaska’s boomed in the 1980s. It’s not enough just to have the oil. There have to be compelling reasons to produce it — economic or otherwise.

“Oil Created the State We Have Today”

The Arctic’s original oil producers are, fittingly, its original inhabitants. An adult bearded seal might yield up to 20 gallons of seal oil (roughly half a barrel). Beyond the tree line, burning seal oil offered Indigenous communities an alternative to wood for light and heat. Unlike the stuff that comes out of the ground, you can eat it, too.

In the late 1970s, as Arctic crude oil began to flow in large quantities, it was Indigenous sealers who found themselves in the sights of environmental activists. Caught up in Greenpeace’s campaign against commercial sealing, Indigenous hunters were vilified and also suffered under eventual bans on imports of seal products by Europe and the US. Greenpeace apologized in 2014, saying the organization needed to “decolonize” itself. In a curious turn of history, a year later Greenpeace offered to help the understandably wary Inuit community of Clyde River in Nunavut, Canada, block exploration for the kind of oil you can’t eat — successfully, as it turned out.

This tension between conservation and development, and between local and global priorities, is inescapable in the Arctic, which is home to a relative handful of people but a symbol to millions more outside of it.

The North Slope Borough is the largest employer and provider of basic services and education in an area that is bigger than 39 states but has a population that would only half-fill Madison Square Garden. More than 90% of its tax revenue derives from oil producers. Talk to Native people who grew up there, and one thing you’ll hear about is the magic of flush toilets appearing around the beginning of the 1980s. Helping Appalachian coal miners figure out a post-carbon future seems relatively straightforward by comparison.

Beyond dollars, oil development touches upon the sensitive issue of agency. While the Willow project is opposed by some on the North Slope, most prominently the mayor of Nuiqsut, the closest village, it appears to enjoy broad support among the Native population. Nagruk Harcharek, president of the Voice of the Arctic Inupiat, a nonprofit bringing together 24 Native communities and organizations across the North Slope, characterizes the board’s deliberation on Willow as “a pretty quick meeting.”

He is critical of outside — a loaded term in Alaska — environmental activists for making Willow a climate cause célèbre. In particular, he challenges simplistic views of the Inupiat lifestyle. “A lot of times, it’s separated, this traditional lifestyle and this Western economy,” he says, but then poses: “How do I go hunting efficiently on a snow machine that isn’t powered by gasoline? What are we going to use for heat in the field? What are we going to use for whaling?”

Native leaders are well aware that climate change is affecting the ground beneath their feet: The fastest recorded increase in permafrost temperatures in Alaska is at Deadhorse. Yet they are also aware that, in the grand scheme of things, their own emissions aren’t going to influence climate change. Even Willow, dubbed a “carbon bomb” by opponents, was found by federal analysts to result in net extra global emissions — accounting for the likelihood of replacement production elsewhere if the project didn’t go ahead — equivalent to just 0.09% and 0.01% of current US and global energy-related emissions, respectively.

“Their choice is not climate change or no climate change. It’s ‘Can we make money and afford to adapt or not?’” says Heather Exner-Pirot, an expert on the Arctic and its Indigenous populations, based in Canada. Drawing a through line from Greenpeace’s conservation colonialism decades ago, she warns that activist campaigns risk creating “an idea that any Arctic development is bad,” adding, “There’s a sense that they [Indigenous people] are living in a theme park.” Even Disneyland has to keep the lights on.

The world has been coming at Indigenous Arctic communities like the villages of the North Slope or Nunavut for a long time in waves: commerce, the military, industrialization, technology, activism. This has brought both costs and benefits and, like anywhere else, views within Indigenous societies differ as to which is which. As the people most exposed to the repercussions of those decisions, they must be heard.

While the North Slope’s situation is more extreme, Alaska overall also remains dependent on oil production, which accounts for roughly a fifth of gross domestic product. That actually understates things, because about 40% to 50% of state revenue comes from oil production, and it also underpins Alaska’s sovereign wealth fund, which issues those famous dividend checks to households and has also plugged budget gaps in recent years. Conoco’s state tax bill alone equated to about 30% of general fund revenue in 2022.

When I met Governor Mike Dunleavy on a gray afternoon in Anchorage in late May, he declared, “Oil created the state we have today.” That jarred a little with the conference we were at on sustainable energy, which his office had organized. But he wasn’t wrong.

Alaska’s initial oil development around the Cook Inlet helped convince Congress that the territory could support itself as a state. The North Slope boom then transformed it. Investment in the Trans-Alaska Pipeline alone was almost four times the state’s entire GDP in 1973. Thor Barker, a maintenance superintendent for Conoco and self-described “fossil,” sums up his choices when he left high school: “You either went to college, to the army or to the Slope.”

Like many a petro-state, Alaska has also suffered a form of Dutch disease, a phrase coined to describe the economic distortions caused by the Netherlands’ discovery of huge deposits of natural gas in the North Sea. Even in the early 1980s, when Alaska’s boom was in full swing, then-Governor Jay Hammond was warning that if Alaskans relied on oil rents to live beyond their means, they would find “we’re much like a cannibal who consumes his own hindquarters and presumes he’s well fed and healthy simply because his belly’s full.”

His imagery, undoubtedly striking, proved unpersuasive. As Roger Marks, a former state petroleum economist, says, “40 years ago, a decision was made: We’re just going to get all our revenue from oil. That was fine until 2016,” when the price crashed. In particular, he says the annual dividend from Alaska’s Permanent Fund has “corrupted” public financing and taxation, making it hard to attract new industries.

Alaska’s metrics have been going the wrong way for a decade, with population flatlining and per capita GDP lower today than in 2009, in real terms. Layer on the threat of a peak in oil demand arriving sooner than expected, and Alaska’s need to remake its economic model is redolent of OPEC members like Saudi Arabia.

Dunleavy’s version of sustainable energy is better thought of as energy that sustains. He does want to foster renewable generation to reduce Alaska’s own high energy costs and thereby entice new industries. He is enthusiastic about a pilot program for a micro-nuclear reactor at Eielson Air Force Base, near Fairbanks. He also wants Alaska to market its forests and depleted oil and gas caverns for carbon sequestration. But, like the Inupiat balancing future transformations with current necessities, he wants to maximize oil and gas revenue now to help get there. That domestic imperative may have found unlikely allies, both at home and abroad.

Thank You, Moscow

The North Slope oil boom owes much to war. President Richard Nixon’s aid airlift to Israel during the Yom Kippur War in October 1973 triggered an Arab embargo and the first oil shock. It’s no accident that the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act that Nixon signed into law the following month declared:

“The early development and delivery of oil and gas from Alaska’s North Slope to domestic markets is in the national interest because of growing domestic shortages and increasing dependence on insecure foreign sources.”

Interest in Alaskan exploration in the first place stemmed in part from an earlier crisis in the Middle East: Suez in 1956. Even then, oil companies had to persevere through multiple (and expensive) dry holes before Prudhoe Bay yielded its secrets. In turn, that discovery brought to a head the long-simmering issue of Native Alaskans’ rights. The 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was the sine qua non of Congress eventually forcing through the construction of the all-important pipeline, which was itself subject to a legislative back-and-forth involving knife-edge votes.

Alaska’s oil boom, therefore, resulted as much from forceful political lever-pulling as it did from the invisible hand — and even then it was a near-run thing. The same holds true, only more so, in Russia, where the Soviet state willed industrialization of its Far North into being. President Vladimir Putin has made Arctic energy exports both a national goal and personal obsession.

Now his invasion of Ukraine, like those 1970s oil shocks, has also reminded the US of Alaska’s strategic value.

The keynote speaker at Dunleavy’s conference was none other than Rahm Emanuel, US ambassador to Japan, former chief of staff to Obama and all-around Republican bête noire. He kicked off by joking that both he and Dunleavy would have to enter witness protection: “Him for inviting me; me for showing up.”

But war makes for strange alliances. Russia’s attack on Ukraine has redrawn the world’s energy map, with the aftershocks of explosions in Kyiv quickly reaching the shores of countries highly dependent on fuel imports — Japan, for instance.

The North Slope has a lot of natural gas but no way to get it to market (unless the US emulates Russia with icebreakers escorting fuel tankers, which was considered in the past but now seems extremely unlikely). Plans to liberate that gas have remained just that for decades. But the Ukraine war has revived such hopes. In April, only a month after approving Willow, the Biden administration green-lit plans by an Alaskan state-owned corporation to build an 807-mile pipeline linking the North Slope to a proposed liquefied natural gas terminal on the Kenai peninsula, just south of Anchorage.

Now all they need is about $40 billion. Ordinarily, that would be a non-starter: LNG export projects don’t usually require the gas to travel the best part of a thousand miles before it even reaches a port. On the other hand, it takes less than 10 days to sail an LNG tanker from Kenai to Japan, so even if the pipeline adds cost, shorter voyages help mitigate that.

Even then, the notorious boom-and-bust cycle in gas markets might deter buyers from signing the long-term contracts needed to win financing. This is where what might be thought of as a security premium comes in. First, a tweak introduced as part of Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act made the proposed LNG pipeline and terminal project eligible for more than $26 billion of federal loan guarantees.

Second, for potential buyers in Asia, such cargoes would come over open sea rather than traversing bottlenecks like the Bering Strait, the Strait of Malacca, or the canals in Panama and Suez. They would also offer a hedge against Russia, the next-closest supplier and not immune from sudden bouts of instability itself. The same goes for oil. While most Alaskan barrels go to the West Coast today — mainly California with its net-zero ambitions — Asia hosts what will likely be the buyers of last resort no matter when or how oil demand peaks.

Emanuel’s pitch that day was nakedly strategic: “If Europe is never going back [to dependence on Russian gas], then our job is to make sure Asia never gets there. … We need to get there first.” Elsewhere in the Arctic, Norway is also pivoting back toward exploration for domestic natural gas to counter Russia’s energy weapon.

I was reminded by Emanuel’s speech, somewhat ironically, of former President Donald Trump’s mantra of “energy dominance.” In any case, it casts Alaska as a means for projecting power — as Russia does with its own Arctic resources — rather than merely the defensive bulwark promoted in the 1970s.

The echo of history is unmistakable. Energy markets are once again fragmenting, casualties of Putin’s war and a wider backlash against globalization. Meanwhile, political support for decarbonization, especially in a sharply divided US, is delicate.

As before, Alaska’s resources represent an insurance policy of sorts, whether against foreign coercion, domestic economic dislocation or local impoverishment. And, not least, they also insure against our latent fears of energy scarcity derailing the larger project of energy transition itself. In the 49th state, the road to net zero, if it is to be both just and secure, must be partly paved with gravel.