Introduction

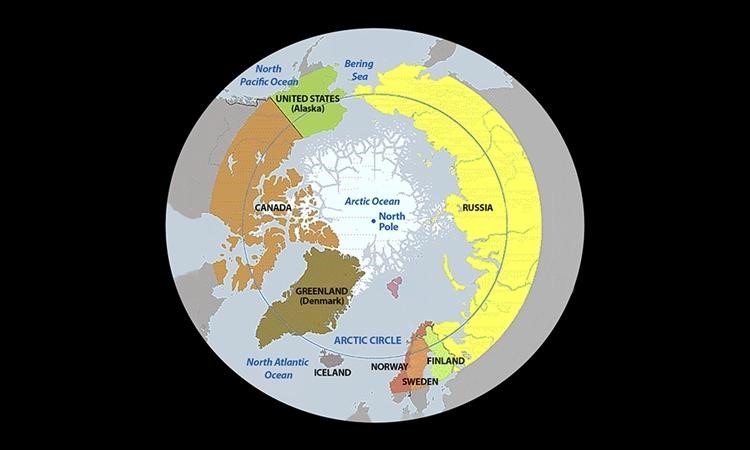

Geographically, the Arctic is the region along the southernmost latitude in the Northern Hemisphere.[1] Politically, it is governed by the eight northernmost states that constitute the Arctic region and are member states of the Arctic Council (see Figure 1): United States (US), Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Russia, Greenland/Denmark, Finland, and Canada.

Figure 1: The Eight Governing States of the Arctic

Source: IARPC Collaborations[2]

Until the 20th century, the remote Arctic had limited economic, transportation, and military viability. Over the past 30 years, the changing climate, increasing scientific exploration, and environmental preservation efforts have brought the region into focus. Arctic warming is taking place at a pace nearly four times higher than the rest of the world,[3] resulting in an unprecedented melting of the polar ice cap and the warming of the area above the Arctic Circle. These changes have economic impacts[4] on Arctic economies and beyond. Existing security challenges have also enhanced the geopolitical significance of the region.

The melting of Arctic ice has created economic prospects, including new transit routes and opportunities for gas and oil drilling.[5] Although Europe has long sought a Northwest Passage (NWP) to Asia, and Russian transport fleets have used the Northern Sea Route (NSR) along Russia’s Arctic coast, the region’s geographical conditions have prevented its widespread use as a transport corridor.[6] However, with travel distances between Eastern Asia and Europe being 40 percent shorter via Arctic passages compared to the Suez Canal and the reduction of sea ice to the point where the Arctic is becoming livable for four to seven months during the summer, the prospect of NSR shipping is resurfacing.[7]

The warming Arctic has also led to increased interest in its natural resources, both offshore and on land. According to the 2008 US Geological Survey,[8] the Circumpolar North contains proven but undiscovered resources of about 90 billion oil barrels, 1,669 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and 44 billion barrels of natural gas liquids. However, the economic potential of Arctic natural gas resources is hindered by the relatively low market value of natural gas compared to oil and the high costs of extraction. Additionally, the remote location of natural gas consumers and the higher transportation costs for natural gas compared to oil and natural gas liquids further complicate its viability. Other challenges to achieving the potential of the Arctic include stringent maritime ecological security regulations, the absence of infrastructure near shipping routes, and limited capacity for search-and-rescue operations.[9]

While the Arctic’s strategic significance has been recognised for decades, security concerns have escalated with deteriorating relations between Russia and the West following the Crimean crisis in 2014 and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.[10] The Russian Federation has increased its overall military capabilities in the Far North. Russia has established nuclear capabilities, including ballistic missile submarines and nuclear warhead storage facilities, in the Kola Peninsula,[11] close to Russia’s border with Norway.

This has alarmed the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and led to unprecedented militarisation in the region.[12] Russia’s military buildup in the Arctic has intensified scrutiny from other Council states about its role as an Arctic Council member and revived discussions about the securitisation of the Arctic.[13]

Following the Ukraine invasion[14] and Sweden’s and Finland’s accession to NATO, the Arctic is being viewed as the next “battlefield”.[15] Sweden’s air capabilities and Finland’s expanded defence budget can contribute to improved cooperation and the region’s collective security.[16] Their membership also underscores NATO’s new northern front, which extends from the Baltic Sea up to the Arctic, which Russia perceives as a direct security threat. Expanded NATO presence and conflicts near the Arctic[17] could drive Moscow to increasingly challenge Western influence, including in the Arctic.

The Arctic Council, though established as a forum for peaceful environmental cooperation and not necessarily for political or security issues, has been challenged by the deteriorating relations between member states. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the other seven Arctic states, all NATO members, refused to operate under Russia’s chairmanship, resulting in a year-long suspension of the Arctic Council. This disruption echoed in the Barents Euro-Arctic Council (BEAC)[18] and the Council of the Baltic Sea States (CBSS)[19] and Russia’s eventual withdrawal from both bodies.

The suspension of the Council’s activities in March 2022 weakened its commitment to cooperation on non-security issues and undermined efforts to prevent geopolitical rivalries.[20] The Council partially resumed work in June 2022, though largely in areas that did not involve Russia;[21] Norway’s chairmanship in 2023 focused on scientific engagement and cooperation with Russia, given their shared borders. Nevertheless, strained relations between Russia and the West have hindered the Council’s ability to address comprehensive pan-Arctic issues that require Russia’s cooperation. This has resulted in debates within the Council on whether it can continue to maintain its cooperative focus amid growing geopolitical frictions in the region. These tensions could undermine the Council’s ability to function as a comprehensive and unified forum, raising concerns about its long-term effectiveness and inclusiveness.

Furthermore, increasing accessibility has led to growing interest and investments from non-Arctic states in the region’s politics. For instance, China has declared itself a “Near-Arctic State”.[22] The US, Russia, and China are also enhancing their military preparations in the region.[23]

India’s Historical Engagement in the Arctic

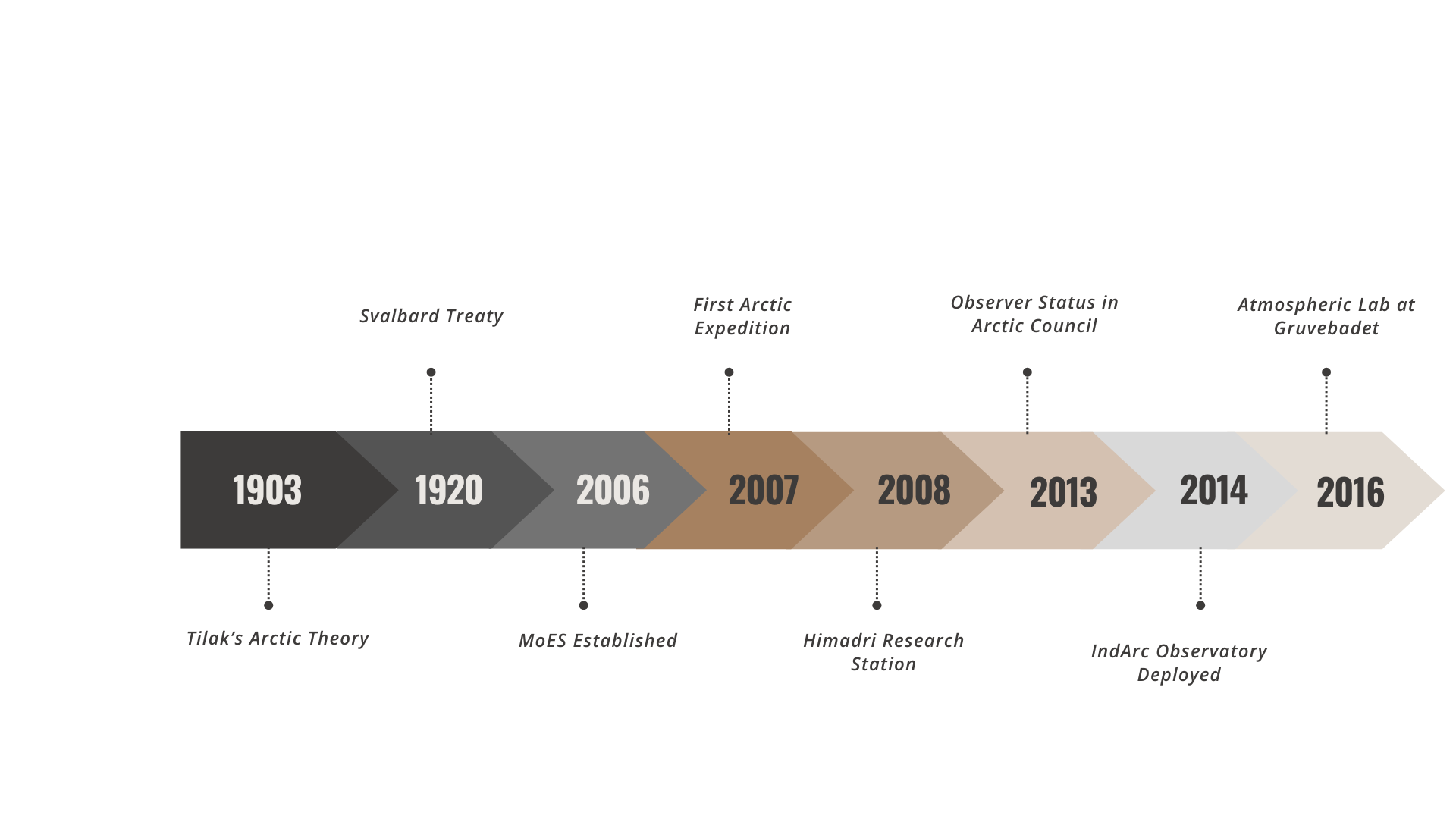

India has long harboured a curiosity about the Arctic region,[a] but its formal Arctic involvement began in February 1920,[24] when it signed the Svalbard Treaty in Paris under the British Empire.[25]In 1981, India established the Department of Ocean Development (DOD), which was tasked with advancing knowledge of the oceans through researching technology to capitalise on marine resources and explore the physical, chemical, and biological components of oceans. In 2006, the DOD was reorganised into the Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES), which had increased authority and financial independence.[26] The MoES was responsible for exploring the oceans and managing resources, both domestically and internationally, and also became the hub for India’s research in the Arctic and Antarctic oceans.[27]

In 2007, India sent its first scientific expedition to the Arctic, with a focus on studying the biology, oceanography, atmosphere, and glaciers in the region. The following year, India established its first Arctic research station, Himadri, at Ny-Alesund in Svalbard, Norway.[28] In 2013, India was granted observer status in the Arctic Council, which allowed it to participate actively in Arctic policy discussions and project undertakings. In 2014, India’s first multi-sensor moored observatory, IndArc, was deployed in Kongsfjorden, and in 2016, an atmospheric laboratory was deployed at Gruvebadet.[29]

Figure 2: Milestones in India’s Arctic Engagement

Source: Author’s own, based on data from the India’s 2022 Arctic Policy[30]

India’s Arctic Policy

India’s initial engagement in the Arctic was driven largely by scientific curiosity. However, with the changing climate and the Arctic’s increasing geopolitical importance, nations are being compelled to rethink their approach to the Arctic, aligning their interests with the region’s evolving landscape.

Though India became an observer in the Arctic Council in 2013, it was one of only four out of the 13 observer nations that did not have a dedicated Arctic policy. In 2021, India released a draft policy, followed by a formal statement from MoES in 2022.[31]

India’s Arctic Policy, which was titled India and the Arctic: Building a Partnership for Sustainable Development,[32] outlines six pillars: strengthening India’s scientific commitment to research, climate, and environmental protection; promoting economic and human development; enhancing transportation and connectivity; improving governance and international cooperation; and building national capacity in Arctic studies.[33]

The Arctic offers potential opportunities for India, including untapped hydrocarbon resources and deposits of minerals such as copper, phosphorus, niobium, platinum group elements, and rare earths.[34] As the world’s third-largest energy consumer, India imports 83 percent of its oil and half of its gas. However, natural gas accounts for just 6 percent of its energy basket, far below the global average of 24 percent. India has a target to increase this share to 15 percent by 2030,[35] and the Arctic offers the energy reserves and potential access to critical minerals, oil, and gas critical for India’s future energy security.

India’s increasing involvement in the Arctic has been occasionally questioned, especially since the country has no direct territorial ties to the region. However, India’s interest can be attributed to its monsoon system, which is influenced by global oceanic and atmospheric changes, including in the Arctic.[36] The melting of the Arctic ice caps has a ripple effect on global weather patterns, including the Indian monsoon.[37] With nearly 60 percent of India’s agriculture dependent on rain-fed systems, stable monsoon patterns are crucial for the nation’s food security and economic well-being.[38] Melting Arctic ice also leads to rising global sea levels, which poses an additional direct threat to India’s 1,300 islands, its coastal regions, and up to 40 million[39] people.

There is also a strategic and scientific interplay between the Arctic and the Himalayas, which India has called the “Third Pole”. While the Himalayan region and the Arctic have different geographies and geopolitical contexts, both are strategically important areas affected by external factors such as geopolitics and increasing conflicts among various upper riparian states.

The Himalayan glaciers feed rivers like Ganga and Brahmaputra, which support 600 million and 177 million people, respectively, while generating over 40 percent of India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).[40] However, the glaciers are melting at an alarming rate, risking an 80-percent loss of their volume[41] and posing a severe risk to rivers that are crucial for many countries in Asia, especially India, Pakistan, and China. Rivers such as the Indus tributaries, which originate in the Himalaya, Karakoram, and Hindu Kush ranges, as well as the area around the Brahmaputra’s Big Bend,[b] are especially vulnerable to glacial retreat.[42] The impact of these transforming glaciers extends beyond climate and economics into the political arena. Historical grievances over water allocation and usage rights already create tensions in the region, with water scarcity and seasonal variations exacerbating existing tensions.[c][43]

The Arctic and the Himalayas also have similar climate concerns.[44] India’s Arctic Policy is centred on climate change, driven by the interdependence between the Arctic, Indian monsoons, and the Himalayan ecosystem.[45] The melting Arctic ice cap offers crucial insights into the behaviour of Himalayan glaciers , including the impacts of black carbon and glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs).[46] Arctic research has also inspired initiatives like the Hindu Kush Himalayan Monitoring and Assessment Programme (HIMAP), modeled after the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP).[47] Additionally, much like the Arctic, the Himalayas face concerns about the release of trapped pathogens, increasing pandemic risks.[48] Therefore, the Arctic could serve as a model[49] for open scientific collaboration and active information sharing, offering lessons for addressing the environmental and strategic challenges in the Himalayas.

The Need for a Seventh Strategic and Geopolitical Pillar in India’s Arctic Policy

While scientific exploration remains the most promising avenue for India-Arctic cooperation, the 2022 Arctic Policy adopted a broader, whole-of-government approach to include climate concerns, economic interests, and governance. It also addressed issues such as the intersection of scientific research and governance, funding, polar research vessels, and infrastructure development. However, it did not address the growing militarisation, great power rivalry, and geopolitical significance of the Arctic. For India to solidify its long-term strategic objectives in the Arctic, the policy must reflect the region’s shifting geopolitical dynamics.[50] Consequently, India could benefit from including a seventh strategic and geopolitical pillar.

Leveraging Economic Opportunities in the Arctic

Melting Arctic ice is reshaping shipping routes, offering a shorter path between economies like the US, Europe, and northeast Asia, resulting in reduced shipping costs, faster transit times, and increased security for goods.[51] While the NSR may not have significant time or distance advantages for India compared to countries like China, South Korea, and Japan, it can still serve as an alternative trade route. Furthermore, India stands to benefit from linking the International North South Transport Corridor (INSTC) with the Unified Deep-Water System (UDWS) of Russia and its further extension to the Arctic.[52] Such connection could lower shipping costs, stimulate hinterland development, and support indigenous communities, offering advantages beyond traditional East–West connectivity.

India is also focusing on developing the Chennai-Vladivostok[53] Eastern Maritime Corridor, which aims to integrate with the NSR. This corridor links the ports of Chennai, Visakhapatnam, and Kolkata in India with Vladivostok, Olga, and Vostochny in Russia, using Vladivostok as a trans-shipment hub before extending to the NSR. By combining this new maritime route with Arctic shipping lanes, trade between India, Russia, and Europe can become faster, more direct, and efficient. The potential of cutting[54] travel time to Europe by two weeks underscores the strategic and economic value of this initiative.

Countering China’s Expanding Presence

For China and Russia, the Arctic is more than an economic frontier; it is a strategic gateway to projecting power across Eurasia. China’s ambitions extend far beyond commerce, as highlighted in its 2018 Arctic Policy white paper[55] which takes a notably more geopolitical stance than India’s policy. Through its “Polar Silk Road” initiative, China strategically links the Arctic to its broader Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) with the broader aim of shielding the Chinese economy from global geopolitical blows and energy-supply disruptions.

China has invested approximately US$10 billion in the Russian Arctic, including in critical energy projects like the Yamal LNG pipeline and Arctic LNG 2. Chinese state-owned enterprises hold a 20 percent stake in these ventures,[56] and collaboration with Russia extends to ice-breaking technology and other advancements. This strategic partnership underscores Beijing’s long-term plans to dominate Arctic shipping lanes.

China’s growing presence in the Arctic, particularly along the NSR, poses strategic challenges to India’s economic and geopolitical interests. Engaging in the Arctic and collaborating with Russia on the NSR can help India counterbalance China’s growing dominance. Such involvement not only hedges against the potential Chinese monopolisation of Arctic shipping lanes that are critical for India’s energy supply line[57] but also prevents an isolated Russia from becoming overly dependent on China. Given India’s strategic concerns about a closer China-Russia partnership, particularly in the context of a potential border conflict with China and its ties to Pakistan, it is imperative for India to strengthen its Arctic presence.[58]

Navigating Geopolitical Dynamics

The Arctic’s evolving landscape is increasingly becoming a theatre for global power play. China’s growing influence in the Arctic, particularly through the NSR, is raising strategic concerns among global security watchers.[59] As China identifies itself as a “near-Arctic state” and pushes its Polar Silk Road initiative, India must respond with strategic precision.[60] While India’s Arctic Policy emphasises sustainability, responsibility, and adherence to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, it must also prioritise its own strategic interests.[61]

India’s participation in the Arctic and its collaboration with Russia on the NSR reinforces its principle of strategic autonomy. By diversifying partnerships, India can maintain its independence while navigating a multipolar global order. Moreover, this engagement offers India an opportunity to counterbalance China’s growing presence in the Arctic and protect its energy supply lines.

India’s 2022 Arctic Policy reflects an understanding of the region’s significance, describing it as an “arena for power and competition”.[62] However, to establish itself as a credible player in the Arctic, India must move beyond policy declarations and take concrete steps to address the region’s geopolitical challenges. Its previous efforts in the Western Pacific have yielded limited results,[d] and the Arctic offers a fresh opportunity to assert its influence. A seventh pillar focused on geopolitics and strategy is, therefore, essential to secure India’s interests in this rapidly transforming region.

India’s Engagement in the Arctic via Nordic and Russian Routes

Although several non-Arctic states have observer status in the Arctic Council, their participation remains largely symbolic, and their influence in Arctic governance remains limited despite the region’s impact on their economic, environmental, and strategic interests.

India has historically maintained a non-aligned stance in the region, striking a balance between the West and Russia and continuing to maintain close ties with both. India’s existing relationships with the Nordics and Russia can be leveraged to further enhance its role in the Arctic and secure a foothold in the region. In order to establish itself as a strategic partner in the region, India must adopt an approach that leverages these relationships to build its influence.

Building trust while advancing strategic interests is crucial for securing a lasting stake in the Arctic. However, India does not need to overlook bilateral relations. Instead, it can foster collaboration by building on existing bilateral relationships.

India-Nordic Relations

India and the Nordic countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland, and Finland) share democratic values, a commitment to pluralism, and strong economic potential. While the Nordic nations lead in innovation, green technologies, and climate action, India has a rapidly growing economy, vast consumer base, rich natural resources, and a dynamic talent pool.[63] Several Nordic multinational companies, including Volvo, IKEA, Tetra Pak, Kone, Wartsila, and Nokia, are active players in the Indian market, and their operations have contributed to economic growth, fostered technology partnerships, and created employment opportunities in India.

The Trade and Economic Partnership Agreement between India and the European Free Trade Association, signed in March 2024, promises to strengthen these economic ties, with commitments of US$100 billion in investments and one million direct jobs projected over the next 15 years.[64] Additionally, most Nordic countries are liberal democracies with strong connections to the West and are aligned in their concerns about the potential threat that China poses to these values.[65] The backlash in the region against China has affected the latter’s investment prospects in the region.[66] This presents India with a strategic advantage over China in cultivating relationships with the Nordic countries and balancing its interests against China’s growing regional influence.

India is one of the few nations to have exclusive summit-level collaborations with the Nordic countries. Although India’s Arctic activities have largely focused on understanding the Arctic’s impact on the Indian monsoons, the India-Nordic relationship is a key factor in furthering India’s Arctic ambitions.[67] Nordic countries make up around 62 percent of all Arctic nations, and an alignment with them would provide India with a valuable foothold in Arctic governance. India’s focus on renewable energy and green technology also aligns with the Nordic expertise.[68] By building on these connections, India and the Nordic countries can advance sustainable development goals, with joint efforts to support renewable energy, climate resilience, and low-carbon shipping solutions.[69] The second India-Nordic summit in 2022 emphasised expanding collaborative efforts under India’s Arctic Policy framework.[70] Climate change, scientific research, and sustainable Arctic tourism[71] emerged as key areas of cooperation, alongside digital connectivity and environmentally friendly shipping routes.

The evolving global security landscape, particularly since Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, has heightened Nordic concerns about the potential for militarisation and geopolitical tensions in the region. Consequently, the Nordic countries are prioritising security partnerships that promote stability without escalating military presence. India, with its commitment to strategic autonomy and a rules-based order, presents a non-militarised, stability-focused ally that aligns well with Nordic interests. India’s peaceful approach and maritime cooperation with a focus on environmental sustainability and scientific research enhances its perception as a valuable partner in promoting Arctic resilience and governance. Collaborative maritime efforts with Nordic countries could improve Arctic navigation, promote sustainable resource use, facilitate clean technology transfer, and advance scientific research on environmental and climate challenges in the region.

Furthermore, the current chair of the Arctic Council, Norway, has resumed official activities within the working groups in a virtual format despite challenges following the Ukraine crisis.[72] With roughly 35 percent of Norway’s landmass situated north of the Arctic, the region holds significant importance for the country. Given Norway’s positive relationship with India, there is potential to further expand cooperation, such as through India’s involvement in initiatives such as research on the global cryosphere, which includes Arctic and other glacier regions.[73] This partnership not only supports Arctic stability but also strengthens India’s voice in shaping the region’s future governance. Together, the Nordic countries and India could act as a strategic pillar for upholding a rules-based international order in the Arctic.

India-Russia Relations

India’s growing interest in the Arctic’s untapped reserves of hydrocarbons and minerals is deeply intertwined with its partnership with Russia. The Russian Federation borders the Arctic region for nearly 50-55 percent of its total length, making much of the untapped resources fall under its jurisdiction. India’s US$15 billion investment in Russian oil and gas projects highlight the growing opportunities in Arctic nations.[74] The investment ensures India’s economic and strategic foothold in a region that is becoming increasingly critical for future resource security. At the 22nd Indo-Russia Summit, both nations expressed a commitment to intensify trade and investment cooperation, particularly in the Russian Far East and Arctic zones. This includes establishing a joint working body within India-Russia Intergovernmental Commission on Trade, Economic, Scientific, Technological, and Cultural Cooperation (IRIGC-TEC) for NSR collaboration, demonstrating India’s ambitions to actively participate in Arctic shipping and energy development and signaling a strategic commitment beyond economic interests.[75] The two countries also agreed to increase bilateral trade to US$100 billion by 2030.[76]

By working closely with Russia on multilateral Arctic forums, India can strengthen its presence in Arctic governance and resource access. Russia’s leadership of the Arctic Council (2021-2023) emphasised regional cooperation and environmental protection.[77] Despite suspended cooperation following the Ukraine invasion, Russian specialists have continued collaborating with observer states like India on renewable energy projects, such as the Snezhinka Arctic station in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Area.[78] These efforts ensure that India remains visibly and strategically present in the Arctic through sustainable development and environmental initiatives.

In parallel, India has increased its imports of Russian crude oil, including lighter grades from the Arctic like ARCO and Novy Port, while enhancing commercial shipping ties. In September 2021, Mazagon Dock Shipbuilders, an Indian government-owned company, signed an agreement with Zvezda, Russia’s largest shipyard, for commercial shipping and shipbuilding.[79] These steps signal India’s strategic entry into Arctic trade networks, expanding its stake in the NSR. Such collaborations also allow India to play an economic role in the Arctic shipping ecosystem, which can contribute to advancing its own shipping and trade capabilities in the region.

Notably, alongside India,[80] China[81] has shown increased interest in becoming a key partner to Russia in developing the NSR. However, China’s expansionist attitude and its enduring interest in Russia’s Far East have consistently hindered the bilateral relationship of the two countries. In this context, India appears as a counterbalance to China, enhancing its strategic importance to Russia and strengthening its role in developing the NSR and Arctic diplomacy. India’s established and neutral relationship with Russia provides a stable and reliable partnership that Russia could leverage to balance China’s expanding influence.[e]

In an evolving global order, marked by a shift in power towards Asia, the India-Russia strategic partnership offers both countries with the opportunity to capitalise on shared interests. As Russia seeks to assert its national identity against Western opposition, Delhi’s strong ties with the West make India a valuable ally.[82] Together, Delhi and Moscow can develop joint projects in the Arctic, where Russia controls nearly 80 percent of the region’s oil and gas reserves while India seeks resources for its growing energy demand.[83] This partnership could fill the emerging power vacuum in the Arctic, advancing broader geopolitical and energy objectives while focusing on resource security and strategic positioning.

Conclusion

India’s Arctic policy, centred around scientific research, environmental protection, and sustainable development, provides a strong foundation but lacks a geopolitical strategy, limiting India’s ability to navigate evolving power dynamics. While India values sustainable resource development, it must balance environmental concerns with strategic imperatives.

Despite leveraging its scientific expertise through initiatives like Himadri and multilateral collaborations, India remains a passive collaborator in Arctic governance. The Arctic is no longer just a domain of scientific interest. The recent “Polar Race” narrative evokes parallels with the 19th-century “Scramble for Africa,” where countries vied for control over resource-rich regions. As global powers like China, Russia, and the US assert dominance, India must move beyond research and establish itself as a trusted stakeholder to safeguard its interests.

A crucial shift to effectively navigate Arctic geopolitics involves institutional recalibration. Currently, India’s Arctic policy falls under the purview of the MoES, while the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) handles the external interface with the Arctic Council. The MEA must take a central role in integrating strategic considerations into policy decisions. Without a comprehensive approach blending science, environment, and geopolitics, India risks marginalisation in the Arctic’s evolving landscape. For India’s global standing and strategic autonomy, strengthening Arctic engagement is not optional but necessary. The choice is whether to act decisively or remain on the periphery of a rapidly transforming geopolitical landscape.

Endnotes

[a] Indian scholar Bal Gangadhar Tilak explored the significance of the Arctic in his 1903 book, The Arctic Home in the Vedas. Tilak traced India’s “Arctic roots” to the Vedic period and stated that the ancient Aryans once lived in the Arctic before migrating south due to climate change. Although controversial, Tilak’s work suggested a broader cultural connection with the Arctic as neither a distant nor disconnected region but one with which India shares a civilisational connection. See: https://archive.org/details/b24864882

[b] Brahmaputra’s Big Bend refers to the sharp U-turn that the river takes around Mount Namcha Barwa in southeastern Tibet before entering India. This area includes southeastern Tibet (China), Arunachal Pradesh (Siang Valley), and Upper Assam, making it hydrologically and geopolitically significant.

[c] For instance, the Indus Waters Treaty between India and Pakistan has regulated water sharing since 1960, but it is often strained by geopolitical conflicts (See: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/9/22/is-the-indus-waters-treaty-the-latest-india-pakistan-flashpoint). Similarly, China’s position upstream on the Brahmaputra has raised concerns in India and Bangladesh over potential water diversions or dam projects.

[d] India’s role in the Western Pacific remains symbolic due to its primary focus on the Indian Ocean, limited ties with ASEAN, and resource constraints that hinder sustained engagement. Additionally, strategic caution to avoid provoking China has further restricted its influence in the region. See: https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2021/08/whats-in-a-name-indias-role-in-the-indo-pacific?lang=en.

[e] According to Sulagna Chattopadhyay, “India and Russia are looking to build resource alliances in the Arctic, particularly in coal and oil. It is important for Russia to hold a robust bi-partite relationship with India on this front, as the closest contender to these resources is China with whom Russia has shared a friendly yet spirited rivalry in the past” (See: https://www.claws.in/arctic-an-emerging-region-of-india-russia-collaboration/ ).

[1] Norwegian Government Agency, Mineral Resources in the Arctic: An Introduction, 2016, https://www.ngu.no/upload/Aktuelt/CircumArtic/Mineral_Resources_Arctic_Shortver_Eng.pdf

[2] Katherine Schexneider, “Arctic Science Explained: Where Is the Arctic?,” IARPC Collaborations, February 2022, https://www.iarpccollaborations.org/news/22412

[3] Jonathan Bamber, “The Arctic Is Warming Nearly Four Times Faster Than the Rest of the World. How concerned Should We Be?,” World Economic Forum, August 2022, https:// www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/08/arctic-warming-four-times-faster-than-world/

[4] Mario Marinov, “The Militarisation of the Arctic and the Growing Importance of the Far North for Great Power Politics,” in Strategic Changes in Security and International Relations, (Bucharest, Romania, 2020), 169-178, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Cristian-Istrate/publication/343537358_CONSEQUENCES_OF_CHINA’S_POWER_RISE_FOR_THE_FUTURE_OF_WORLD_AFFAIRS/links/5f2fb457458515b7290fde7e/CONSEQUENCES-OF-CHINAS-POWER-RISE-FOR-THE-FUTURE-OF-WORLD-AFFAIRS.pdf

[5] Ekaterina Klimenko, “The Geopolitics of a Changing Arctic,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2019, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep20067

[6] Marinov, “The Militarisation of the Arctic and the Growing Importance of the Far North for Great Power Politics”.

[7] Halvor Schøyen, “The Northern Sea Route Versus the Suez Canal: Cases From Bulk Shipping,” Journal of Transport Geography, 2011, https://www.sciencedirect.com/ science/article/abs/pii/S096669231100024X

[8] US Government, Circum-Arctic Resource Appraisal: Estimates of Undiscovered Oil and Gas North of the Arctic Circle, (U.S. Geological Survey, 2008), https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/ fs20083049

[9] Klimenko, “The Geopolitics of a Changing Arctic”.

[10] Andreas Østhagen et al., “Arctic Geopolitics: The Svalbard Archipelago,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), 2023, http:// www.jstor.org/stable/resrep53126

[11]Thomas Nilsen, “Putin Puts Nuclear Deterrence Forces at Kola Peninsula on Alert,” The Barents Observer, February 27, 2022, https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/security/putin-puts-nuclear-deterrence-forces-at-kola-peninsula-on-alert/163588

[12] Marinov, “The Militarisation of the Arctic and the Growing Importance of the Far North for Great Power Politics”

[13]Colin Wall and Njord Wegge, “The Russian Arctic Threat: Consequences of the Ukraine War,” Centre for Strategic and International Studies, January 25, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russian-arctic-threat-consequences-ukraine-war

[14] Sakshi Tiwari, “US, Russia Boost Military Presence Around North Pole; Experts Say After Ukraine, Arctic Could Be The Next ‘Battleground’,” Eurasian Times, October 2022, https://www.eurasiantimes.com/us-russia-boost-military-presence-around-north-pole- experts/.

[15] Sydney Murkins, “The Future Battlefield Is Melting: An Argument for Why the U.S. Must Adopt a More Proactive Arctic Strategy,” The Arctic Institute- Center for Circumpolar Security Studies, December 3, 2024, https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/future-battlefield-melting-argument-us-must-adopt-more-proactive-arctic-strategy/

[16]Janne Kuusela, “As a New Arctic Ally, Finland Contributes to Arctic Security and Defence,” Wilson Centre, March 1, 2024, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/no-25-new-arctic-ally-finland-contributes-arctic-security-and-defence

[17] Arti Kumari, “Growing Military Presence in the Arctic,” Defence Research and Studies, April 2023, https://dras.in/growing-military-presence-in-the-arctic/

[18] “Russia Withdraws from Barents Euro-Arctic Council,” Arctic Portal, September 19, 2023, https://arcticportal.org/ap-library/news/3328-russia-withdraws-from-barents-euro-arctic-council

[19] “Russia Withdraws from Council of Baltic Sea States- Foreign Ministry Statement,” TASS Russian News Agency, May 17, 2022, https://tass.com/politics/1452051

[20]Ankita Dutta, “Norway’s Arctic Council Chairship: Priorities vs Geopolitics,” Observer Research Foundation, June 3, 2023, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/norways-arctic-council-chairship

[21]Department of State, United States of America, https://www.state.gov/joint-statement-on-limited-resumption-of-arctic-council-cooperation/

[22]David Merkel, “The Self-Proclaimed Near-Arctic State,” Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, April 18, 2022, https://www.kas.de/en/web/auslandsinformationen/artikel/detail/-/content/der-selbsternannte-fast-arktisstaat

[23] Matthew Melino et al., “The Ice Curtain; Russia’s Arctic Military Presence,” Centre for Strategic and International Studies, March 26, 2020, https://www.csis.org/features/ice-curtain-russias-arctic-military-presence

[24] Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India, India’s Arctic Policy: Building a Partnership for Sustainable Development, (New Delhi: Ministry of Earth Sciences, March 17, 2022), https://www.moes.gov.in/sites/. default/files/2022-03/compressed-SINGLE-PAGE-ENGLISH.pdf

[25] Nitin Agarwala, “India and the Arctic: Evolving Engagements,” Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS) 4, no. 2, October 2022, https:// ris.org.in/newsletter/sdr/2023/Article-1.pdf

[26] Sinha U. Kumar, “India in the Arctic: A Multidimensional Approach,” Вестник Санкт- Петербургского университета, Международные отношения, 2019, https:// cyberleninka.ru/article/n/india-in-the-arctic-a-multidimensional-approach

[27] Kumar, “India in the Arctic: A Multidimensional Approach”.

[28] Ministry of Earth Sciences, India’s Arctic Policy: Building a Partnership for Sustainable Development.

[29] Ministry of Earth Sciences, India’s Arctic Policy: Building a Partnership for Sustainable Development.

[30] Ministry of Earth Sciences, India’s Arctic Policy: Building a Partnership for Sustainable Development.

[31] Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India, https://www.pib.gov.in/ PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1806993

[32] Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India, https://www.pib.gov.in/ PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1806993

[33] Manish Singh, “India in the Arctic: Legal Framework and Sustainable Approach,” The Arctic Institute- Center for Circumpolar Security Studies, January 9, 2024, https:// www.thearcticinstitute.org/india-arctic-legal-framework-sustainable-approach/

[34] Ministry of Earth Sciences, India’s Arctic Policy: Building a Partnership for Sustainable Development.

[35] IEA, India Energy Outlook 2021, World Energy Outlook Special Report, February 2021, Paris, International Energy Agency, 2021, https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/1de6d91e-e23f-4e02-b1fb-51fdd6283b22/India_Energy_Outlook_2021.pdf

[36] Shailesh Nayak, “Polar Research in India,” Indian Journal of Marine Sciences 37, no. 4, December 2008: 352-357, https://nopr.niscpr.res.in/bitstream/123456789/3358/1/IJMS%2037%284%29%20352-357.pdf

[37] Newton Sequeira, “Melting Sea Ice In Arctic Linked to Indian Monsoon, Study May Help Better Forecasts,” The Times of India, June 30, 2024, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/ city/goa/melting-sea-ice-in-arctic-linked-to-indian-monsoon-study-may-help-better- forecasts/articleshow/111370339.cms

[38] Kumar, “India in the Arctic: A Multidimensional Approach”.

[39]Omair Ahmad, “Linking the Arctic to the Himalayas,” Dialogue Earth, January 30, 2017 https://dialogue.earth/en/climate/linking-the-arctic-to-the-himalayas/

[40] Ministry of Earth Sciences, India’s Arctic Policy: Building a Partnership for Sustainable Development.

[41] “Himalayan Glaciers Could Lose 80% of their Volume If Global Warming Isn’t Controlled, Study Finds,” The Hindu, June 22, 2023, https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/energy-and-environment/himalayan-glaciers-could-lose-80-of-their-volume-if-global-warming-isnt-controlled/article66996679.ece

[42] Walter W. Immerzeel et al., “Climate Change Will Affect the Asian Water Towers,” American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), June 11, 2010, https://www.futurewater.nl/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Immerzeel_Science_11June2010.pdf

[43]Brahma Chellaney, Water: Asia’s Next Battleground (Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 2011).

[44]Dagfinnur Sveinbjörnsson, “The Arctic and Third Pole – Himalaya: Science and Collaboration,” Arctic Circle, January 19, 2022, https://www.arcticcircle.org/journal/the-arctic-and-third-pole-himalaya

[45] Abhijnan Rej, “India Releases Draft Arctic Policy,” The Diplomat, January 5, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/01/india-releases-draft-arctic-policy/

[46] Muthukumara Mani, Glaciers of the Himalayas: Climate Change, Black Carbon, and Regional Resilience, Washington DC, World Bank Group, 2021, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/976841622778070962/pdf/Glaciers-of-the-Himalayas-Climate-Change-Black-Carbon-and-Regional-Resilience.pdf

[47] Sveinbjörnsson, “The Arctic and Third Pole – Himalaya: Science and Collaboration”.

[48] “Melting Himalayan Ice Reveals 1,700 Ancient and Unknown Virus Species,” The Times of India, September 3, 2024, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/etimes/trending/melting-himalayan-ice-reveals-1700-ancient-and-unknown-virus-species/articleshow/113009643.cms

[49] Ibsen Thórir, The Arctic Cooperation, a Model for the Himalayas—Third Pole? (Springer Cham, 2018), pp. 3-16.

[50] Rej, “India Releases Draft Arctic Policy”.

[51] Singh, “India in the Arctic: Legal Framework and Sustainable Approach”.

[52] Ministry of Earth Sciences, India’s Arctic Policy: Building a Partnership for Sustainable Development

[53] Sinderpal Singh, “India, Russia, and the Northern Sea Route: Navigating a Shifting Strategic Environment,” S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), September 5, 2023, https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp- content/uploads/2023/09/CO23125.pdf

[54] Ram Singh, “It’s time for India to Invest in Maritime Corridor Through North Sea Route,” Business Standard, October 3, 2024, https://www.business-standard.com/ opinion/columns/it-s-time-for-india-to-invest-in-maritime-corridor-through-north-sea- route-123092500417_1.html

[55] The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, “China’s Arctic Policy,” January 26, 2018, https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2018/01/26/ content_281476026660336.htm

[56] “Chinese Banks Ready to Invest $10 Billion in Yamal LNG,” The Moscow Times, November 7, 2014, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2014/11/07/ chinese-banks-ready-to-invest-10-billion-in-yamal-lng-a41134

[57] Singh, “India in the Arctic: Legal Framework and Sustainable Approach”.

[58] Singh, “India, Russia, and the Northern Sea Route: Navigating a Shifting Strategic Environment”.

[59] “A Balanced Approach to the Arctic—A Conversation with U.S. Coordinator for the Arctic Region James P. DeHart,” The Foreign Service Journal, May 2021,

[60] Rej, “India Releases Draft Arctic Policy”.

[61] Rej, “India Releases Draft Arctic Policy”.

[62]David Auerswald, “China’s Multifaceted Arctic Strategy,” War on the Rocks, May 24, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/05/chinas-multifaceted-arctic-strategy/

[63] Debasis Bhattacharya, “India-Nordic relations: A mutual Outreach,” Observer Research Foundation, June 4, 2022, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/india-nordic-relations

[64] Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/ PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=2013169

[65]Andreas B. Forsby, “Falling Out of Favor: How China Lost the Nordic Countries,” The Diplomat, June 24, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/06/falling-out-of-favor-how-china-lost-the-nordic-countries/

[66]Patrik Andersson, “The Recent Backlash Against China in the Nordic Arctic: Prospects for Future Chinese Engagement in the Region,” Swedish National China Centre, June 13, 2024, https://kinacentrum.se/en/publications/the-recent-backlash-against-china-in-the-nordic-arctic-prospects-for-future-chinese-engagement-in-the-region/

[67] Shakti P. Srichandan and Pooja Mohanty, “India in the Arctic through the Nordic Route,” Financial Express, May 16, 2024, https://www.financialexpress.com/business/defence/ india-in-the-arctic-through-the-nordic-route/3490719/

[68] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/35276/Joint_Statement__2nd_IndiaNordic_Summit#:~:text=During%20the%20Summit%2C%20the%20Prime,and%20climate%20change%2C%20the%20blue

[69] “India, Nordic Countries Agree to Remain Engaged on Ukraine,” The Print, May 05, 2022, https://theprint.in/world/india-nordic-countries-agree-to-remain-engaged- on-ukraine/943033/

[70] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, https:// www.mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/35277/2nd_IndiaNordic_Summit

[71] “Sustainable Arctic Tourism,” Arctic Portal, https:// portlets.arcticportal.org/tourisminthearctic/54-tourism

[72] “Arctic Council Advances Resumption of Project-Level Work,” Arctic Council, February 28, 2024, https://arctic-council.org/news/arctic-council-advances-resumption-of-project-level-work/#:~:text=In%20resuming%20virtual%20Working%20Group,ensure%20project%2Dlevel%20work%20advancement

[73] Huma Siddiqui, “India-Norway Ties Set to Soar at the India-Nordic Summit: A Partnership for a Sustainable Future,” Financial Express, September 9, 2024, https://www.financialexpress.com/business/industry-india-norway-ties-set-to-soar-at-the-india-nordic-summit-a-partnership-for-a-sustainable-future-3605317/

[74] Sahana Ghosh and Mayank Aggarwal, “With a New Policy, India Aims to Understand the Impact of the Arctic Region on its Monsoon,” Quartz, January 24, 2021, https://qz.com/ india/1939274/indias-arctic-policy-to-focus-on-climate-change-monsoon-rains

[75] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/ 37940/ Joint+Statement+following+the+22nd+IndiaRussia+Annual+Summit#:~:text=In%20this% 20 regard%2C%20the%20 Sides,zone%20of%20the%20 Russian%20 Federation

[76] Suhasini Haidar, “India, Russia to Boost Bilateral Trade to $100 billion by 2030,” The Hindu, July 9, 2024, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/india-russia-to-boost- bilateral-trade-to-100-billion-by-2030/article68386101.ece

[77] Emilie Canova and Pauline Pic, “The Arctic Council in Transition: Challenges and Perspectives for the New Norwegian Chairship,” The Arctic Institute- Center for Circumpolar Security Studies, June 13, 2023, https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/arctic- council-transition-challenges-perspectives-new-norwegian-chairship/

[78] “The Arctic Project “Snowflake” Will be Implemented in Any Case,” RIA Novosti, June 15, 2022, https://ria.ru/20220615/arktika-1795372600.html?in=t

[79] Capital Market, “Mazagon Dock Soars After Partnership with Russia’s Zvezda for Commercial Ships,” Business Standard, September 3, 2021, https://www.business- standard.com/article/news-cm/mazagon-dock-soars-after-partnership-with-russia-s- zvezda-for-commercial-ships-121090300803_1.html

[80] Jawahar V. Bhagwat and Natalia Viakhireva, “India Considers Northern Sea Route Potential,” Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC), July 31, 2024, https:// russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/interview/india-considers-northern-sea- route-potential/

[81] “Russia Teams with China for Development of the Northern Sea Route,” The Maritime Executive, May 19, 2024, https://maritime- executive.com/article/russia-teams-with-china-for-development-of-the-northern-sea- route

[82] Hriday Sarma, “Arctic: An Emerging Region of India-Russia Collaboration,” Centre for Land Warfare Studies, December 27, 2023, https://www.claws.in/arctic-an- emerging-region-of-india-russia-collaboration/

[83] Anna Kireeva, “For All of Russia’s Talk About Oil Drilling in the Arctic, Most Arctic Oil Will Likely Go Untouched,” Bellona, April 24, 2019, https://bellona.org/news/arctic/2019-04-for- all-of-russia’s-talk-about-oil-drilling-in-the-arctic-most-arctic-oil-will-likely-go-untouched#:~:text=Indeed%2C%20among%20Arctic%20nations%2C%20Russia%27s,remaining%2010%20percent%20among%20them