Despite the EU having little direct say on the protection of poles and glaciers, advocates argued at the One Planet – Polar Summit, hosted in Paris from Wednesday to Friday (8-10 November), that its economic might can still be influential.

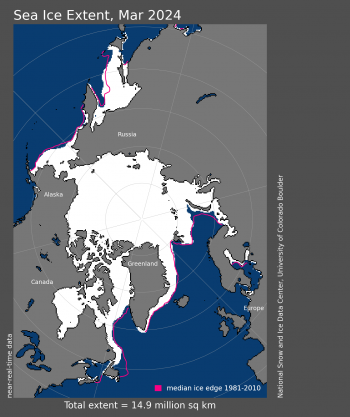

Rising sea levels and coastal flooding are directly linked to the Arctic’s warming. According to a study published in August 2022, the region is warming four times faster than the rest of the world.

By the end of the century, few countries will be able to escape it – even in Europe.

France, which is particularly exposed with its three coasts and 11 million km2 of maritime space spread over its territories in the four corners of the globe, hosted the One Planet -Polar Summit in Paris from Wednesday to Friday (8 -10 November).

This first global summit dedicated to the protection of the cryosphere was an opportunity to reaffirm the importance of protecting the polar and glacial zones by drastically reducing or even banning the exploitation of their resources.

But while France is at the forefront of efforts to protect the region, it cannot act alone.

French President Emmanuel Macron expressed his opposition to deep-sea mining permits but confirmed his support for exploration at the recent COP27 summit in Egypt, settling the matter of France’s stance once and for all.

EU objectives

This is where the European Union comes in. The EU’s Arctic policy, last updated on 13 October 2021, states that protecting the Arctic is essential to achieving the bloc’s climate objectives, adding: “The EU’s full engagement in Arctic matters is a geopolitical necessity”.

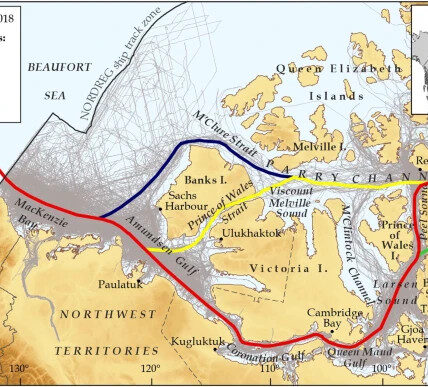

This mainly involves a more sustainable use of the region’s fisheries resources and potential restrictions on exploiting fossil and mining resources there.

The EU has exclusive competence in managing fisheries resources and as such, can regulate the activities of Sweden and Finland, two member states with large Arctic territories.

But when it comes to exploiting fossil and mineral resources, the EU’s capacity is limited.

In addition, other neighbouring countries have strong interests in the Arctic, most notably Iceland and Norway, which are members of the European Economic Area. So do China, Russia, the United States, Canada, Japan and South Korea.

So how can the EU influence the environmental policies of these countries when “geopolitically it is still far from being a major player in the region”? This is the question posed by Geneviève Pons, Director General of the Institut Europe Jacques Delors and former Director of WWF Europe.

In her view, the EU has a significant advantage: its economic power as the world’s leading trading centre.

EU influence

This position gives it influence insofar as the sustainability requirements it imposes on products entering its market can influence the policies of its partners.

The EU is well aware of this and, over the last few years, has been introducing one piece of legislation after another: the Ecodesign Directive for products entering the EU market is currently being updated, negotiations on corporate due diligence are ongoing, legislation banning deforestation-derived products is due to be adopted in December 2022, and a border carbon tax has been introduced.

Underscoring the fears raised by these rules, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen in August said that her department was “concerned about the extraterritorial reach of the due diligence directive” and would “make that clear to the EU”.

In a similar vein, China is “trying to understand what the EU’s environmental requirements are to maintain its activity in the Community market,” says Pons.

In particular, the EU has taken an interest in the environmental and social traceability of batteries for electric vehicles, one of the flagship products of Sino-European trade.

The entry of Chinese batteries into the EU market could, therefore, be hampered if it turns out that their production requires the exploitation of Arctic land and seas or other areas that the EU wants to protect.

Pons already sees a change of heart on the Chinese side, saying Beijing is interested in protecting a large area in South Antarctica.

Germany’s Rhine region got a foretaste of things to come during the 2018 summer drought. And it doesn’t look good.

What about Russia?

This optimism is not shared by all stakeholders, however.

While Europe can influence the position of countries like Norway on issues, like the exploitation of hydrocarbons in Arctic zones, the situation is very different for Russia.

Moscow has established itself as a key regional player geographically, environmentally and militarily. But the invasion of Ukraine has made talks impossible, even though Russia steps down as the Arctic Council Chair, a key forum for cooperation in the region.

So, the stakes are eminently geopolitical.

For French Ecological Transition Minister Christophe Béchu, the management of the Arctic is “not only an environmental issue but at the crossroads of everything that gives rise to the need to preserve and protect humanity”, pointing out that international and national tensions are bound to increase as the cryosphere warms.

In his view, the One Planet – Polar Summit should serve as a “sounding board for COP28” because “the best way to be ambitious about melting ice is to be ambitious about COP28”.

Still, getting Russia to engage positively at COP28 will not be an easy task in view of the Ukraine conflict.

“We can see how difficult this will be with all the geopolitical challenges facing the world,” warned EU climate chief Wopke Hoekstra at the European Climate Stocktake event last month.